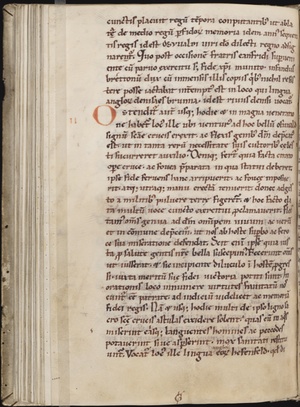

This image from Yale University, Beinecke Library MS 330, fol. 56v, a copy of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica, appears in accordance with the Beinecke’s use policies

Geoffrey of Monmouth

and British History

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

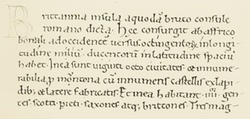

Historia Naturalis (The Natural History): IV.xvi

Pliny the Elder (c. 23 - 79 AD)

The portrait of Pliny is taken from a 1635 printing of the Historia Naturalis; the initial is from a 1559 printing. Both of these editions are in Rare Books and Special Collections. To see how the description of Britain looks in these and other old printings in the UBC collection, go to the page Pliny at UBC.

pposite this region lies the island of Britain, famous in Greek records and in our own. It lies between the northern regions and the west, across a wide channel from Germany, Gaul, and Spain: these make up the greater part of Europe. It was called Albion, while all the islands around it, about which we shall speak briefly soon, were called the Britains. It is 50 miles from Gesoriacum [Boulogne] on the shores of the Morini people, by the shortest passage. Pytheas and Isidorus say that its circumference is 4875 miles. Almost 30 years ago, its exploration was carried out by Roman armies — an exploration extending no further than the Caledonian forests. Agrippa believes the length of the island to be 800 miles and its breadth, 300; and the breadth of Ireland to be the same, but 200 miles less in longitude. Ireland is beyond Britain, and the shortest crossing is from the area of the Silures, a crossing of 30 miles.... The most remote of all the remaining islands is Thule [Norway?], in which, as we have indicated, there are no nights in midsummer, when the sun is passing through the sign of the Crab; and indeed there are no days in midwinter....

pposite this region lies the island of Britain, famous in Greek records and in our own. It lies between the northern regions and the west, across a wide channel from Germany, Gaul, and Spain: these make up the greater part of Europe. It was called Albion, while all the islands around it, about which we shall speak briefly soon, were called the Britains. It is 50 miles from Gesoriacum [Boulogne] on the shores of the Morini people, by the shortest passage. Pytheas and Isidorus say that its circumference is 4875 miles. Almost 30 years ago, its exploration was carried out by Roman armies — an exploration extending no further than the Caledonian forests. Agrippa believes the length of the island to be 800 miles and its breadth, 300; and the breadth of Ireland to be the same, but 200 miles less in longitude. Ireland is beyond Britain, and the shortest crossing is from the area of the Silures, a crossing of 30 miles.... The most remote of all the remaining islands is Thule [Norway?], in which, as we have indicated, there are no nights in midsummer, when the sun is passing through the sign of the Crab; and indeed there are no days in midwinter....

You can find the Latin text online at Bill Thayer’s LacusCurtius site, a large site devoted to images and texts of the Roman world.

For still more pictures: there are 3 images from a 16th-century printing of the Naturalis Historia on the Smithsonian's site for its wonderful Voyages exhibit. The Pliny images are in the Journeys over land and sea: Botany and zoology subsection.

De excidio et conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain)

Gildas (c. 504 - 570)

The island of Britain, situated on almost the utmost border of the earth, towards the south and west, and poised in the divine balance, as it is said, which supports the whole world, stretches out from the south-west towards the north pole, and is eight hundred miles long and two hundred broad, except where the headlands of sundry promontories stretch farther into the sea. It is surrounded by the ocean, which forms winding bays, and is strongly defended by this ample, and, if I may so call it, impassable barrier, save on the south side, where the narrow sea affords a passage to Belgic Gaul. It is enriched by the mouths of two noble rivers, the Thames and the Severn, as it were two arms, by which foreign luxuries were of old imported, and by other streams of less importance. It is famous for eight and twenty cities, and is embellished by certain castles, with walls, towers, well barred gates, and houses with threatening battlements built on high, and provided with all requisite instruments of defence. Its plains are spacious, its hills are pleasantly situated, adapted for superior tillage, and its mountains are admirably calculated for the alternate pasturage of cattle, where flowers of various colours, trodden by the feet of man, give it the appearance of a lovely picture. It is decked, like a man's chosen bride, with divers jewels, with lucid fountains and abundant brooks wandering over the snow white sands; with transparent rivers, flowing in gentle murmurs, and offering a sweet pledge of slumber to those who recline upon their banks, whilst it is irrigated by abundant lakes, which pour forth cool torrents of refreshing water.

There are many excerpts of this text online: see, for example, The Medieval Sourcebook: Gildas. There is a Latin version online as well: Gildas: de excidio et conquestu britanniae.

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People)

Bede, 713

You can see a medieval translation of Bede into Old English at Oxford’s Early Manuscripts at Oxford University project; the manuscript is Corpus Christi College 279B.

Bede’s World is a museum in Jarrow devoted to Bede's period: you might find their website interesting.

You can find the full text of the Historia ecclesiastica online at The Internet Medieval Sourcebook: Bede

RITAIN, an island in the ocean, formerly called Albion, is situated between the north and west, facing, though at a considerable distance, the coasts of Germany, France, and Spain, which form the greatest part of Europe. It extends 800 miles in length towards the north, and is 200 miles in breadth, except where several promontories extend further in breadth, by which its compass is made to be 3675 miles.... On the back of the island, where it opens upon the boundless ocean, it has the islands called Orcades. Britain excels for grain and trees, and is well adapted for feeding cattle and beasts of burden. It also produces vines in some places, and has plenty of land and waterfowls of several sorts; it is remarkable also for rivers abounding in fish, and plentiful springs. It has the greatest plenty of salmon and eels; seals are also frequently taken, and dolphins, as also whales; besides many sorts of shellfish, such as mussels, in which are often found excellent pearls of all colours, red, purple, violet, and green, but mostly white. There is also a great abundance of cockles, of which the scarlet dye is made; a most beautiful colour, which never fades with the heat of the sun or the washing of the rain; but the older it is, the more beautiful it becomes. It has both salt and hot springs, and from them flow rivers which furnish hot baths, proper for all ages and sexes, and arranged according. For water, as St. Basil says, receives the heating quality, when it runs along certain metals, and becomes not only hot but scalding. Britain has also many veins of metals, as copper, iron, lead, and silver; it has much and excellent jet, which is black and sparkling, glittering at the fire, and when heated, drives away serpents; being warmed with rubbing, it holds fast whatever is applied to it, like amber. The island was formerly embellished with twentyeight noble cities, besides innumerable castles, which were all strongly secured with walls, towers, gates, and locks. And, from its lying almost under the North Pole, the nights are light in summer, so that at midnight the beholders are often in doubt whether the evening twilight still continues, or that of the morning is coming on...

RITAIN, an island in the ocean, formerly called Albion, is situated between the north and west, facing, though at a considerable distance, the coasts of Germany, France, and Spain, which form the greatest part of Europe. It extends 800 miles in length towards the north, and is 200 miles in breadth, except where several promontories extend further in breadth, by which its compass is made to be 3675 miles.... On the back of the island, where it opens upon the boundless ocean, it has the islands called Orcades. Britain excels for grain and trees, and is well adapted for feeding cattle and beasts of burden. It also produces vines in some places, and has plenty of land and waterfowls of several sorts; it is remarkable also for rivers abounding in fish, and plentiful springs. It has the greatest plenty of salmon and eels; seals are also frequently taken, and dolphins, as also whales; besides many sorts of shellfish, such as mussels, in which are often found excellent pearls of all colours, red, purple, violet, and green, but mostly white. There is also a great abundance of cockles, of which the scarlet dye is made; a most beautiful colour, which never fades with the heat of the sun or the washing of the rain; but the older it is, the more beautiful it becomes. It has both salt and hot springs, and from them flow rivers which furnish hot baths, proper for all ages and sexes, and arranged according. For water, as St. Basil says, receives the heating quality, when it runs along certain metals, and becomes not only hot but scalding. Britain has also many veins of metals, as copper, iron, lead, and silver; it has much and excellent jet, which is black and sparkling, glittering at the fire, and when heated, drives away serpents; being warmed with rubbing, it holds fast whatever is applied to it, like amber. The island was formerly embellished with twentyeight noble cities, besides innumerable castles, which were all strongly secured with walls, towers, gates, and locks. And, from its lying almost under the North Pole, the nights are light in summer, so that at midnight the beholders are often in doubt whether the evening twilight still continues, or that of the morning is coming on...

This island at present, following the number of the books in which the Divine law was written, contains five nations, the English, Britons, Scots, Picts, and Latins, each in its own peculiar dialect cultivating the sublime study of Divine truth. The Latin tongue is, by the study of the Scriptures, become common to all the rest. At first this island had no other inhabitants but the Britons, from whom it derived its name, and who, coming over into Britain, as is reported, from Armorica, possessed themselves of the southern parts thereof....

Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons)

“Nennius,” c. 800

The full text is available online in translation in the Medieval Sourcebook: Nennius.

The island of Britain is so called from one Brutus, a Roman consul. It reaches from the south-west northward, and lies to the west. It is 800 miles long, 200 broad. In it are twenty-eight cities and headlands without number, together with innumerable forts built of stone and brick, and in it live four nations, the Irish, the Picts, the Saxons and the British.

It has three large islands. One of them lies towards Armorica, and is called the Isle of Wight; the second is situated in the middle of the sea between Ireland and Britain, and is named Eubonia, that is Man; the other is situated at the extreme edge of the world of Britain, beyond the Picts, and is called Orkney. So the old saying runs, when rulers and kings are mentioned, "He ruled Britain with its three islands."

In Britain there are many rivers, that flow in all directions, to the east, west, south and north. But two of the rivers excel beyond the rest, the Thames and Severn, like the two arms of Britain, on which ships once travelled, carrying goods for the sake of commerce. The British once occupied and ruled it all from sea to sea.

Bede on the languages and peoples of Britain (I.i)

[Britain] has five languages, just as the divine law is written in five books. These are the English, Welsh, Irish, Pictish, and Latin languages: all are devoted to examining and setting forth the knowledge of the highest truth and of true sublimity – but Latin, by means of the study of scriptures, has become common to all.

Geoffrey on the peoples of Britain (I.iii)

Lastly, Britain is inhabited by five races of people, the Norman-French, the Britons, the Saxons, the Picts, and the Scots. Of these the Britons once occupied the land from sea to sea, before the others came. Then the vengeance of God overtook them because of their arrogance and they submitted to the Picts and the Saxons.

Bede on the stakes in the Thames (I.ii)

The Romans saw and avoided [the stakes], so the barbarians, being unable to resist the charge of the legions, hid themselves in the woods, from which they made constant sallies and frequently did the Romans great damage.

Nennius on the stakes in the Thames (c 20)

This unseen contrivance was a decisive danger to the Roman soldiers, and they went away without peace on that occasion

Geoffrey on the stakes in the Thames (IV.vii)

As [Caesar] cruised up the Thames in the direction of the above-mentioned city of Trinovantum his ships ran upon the stakes which I have described and so suffered their moment of sudden jeopardy. Thousands of soldiers were drowned as river-water flowed into the holed ships and sucked them down. When Caesar discovered what was happening he made every effort to furl his sails and then ran ashore as fast as he could. Those survivors who by the skin of their teeth had escaped from so great a peril now clambered with Caesar on to dry land.

Gildas on St. Alban (c 11)

Alban, for charity’s sake, and in imitation even here of Christ, who laid down his life for his sheep, protected a confessor from his persecutors when he was on the point of arrest. Hiding him in his house and then changing clothes with him, he gladly exposed himself to danger and pursuit in the other's habit. Between the time of his holy confession and the taking of his blood, and in the presence of wicked men who displayed the Roman standards to the most horrid effect, the pleasure that God took in him showed itself: by a miracle he was marked out by wonderful signs. Thanks to his fervent prayer, he opened up an unknown route across the channel of the great river Thames – a route resembling the untrodden way made dry for the Israelites, when the ark of the testament stood for a while on gravel in the midstream of Jordan. Accompanied by a thousand men, he crossed dry-shod, while the river eddies stayed themselves on either side like precipitous mountains.

Geoffrey on St. Alban (V.v)

Albanus, glowing bright with the grace of charity, first hid his confessor Amphibalus in his own house, when the latter was closely pursued by his persecutors and on the point of being taken; and then changed clothes with him and offered himself to Death’s final parting, thus emulating Christ who laid down His own life for His sheep.

Gildas on the appeal of the Britons (c 20)

Igitur rursum miserae mittentes epistolas reliquiae ad Agitium Romanae potestatis virum, hoc modo loquentes: ‘Agitio ter consuli gemitus Britannorum;’ et post pauca querentes: ‘repellunt barbari ad mare, repellit mare ad barbaros; inter haec duo genera funerum aut iugulamur aut mergimur;’ nec pro eis quicquam adiutorii habent.

Note that the spelling differences in these two versions are in part due to the use of classical (eg., the -ae ending) rather than medieval spelling

Geoffrey on the appeal of the Britons (VI.iii; c. 91 in Wright)

Igitur rursum misere reliquie mittunt epistulas ad Agitium, Romane potestatis uirum, hoc modo loquentes:

‘Agitio ter consuli gemitus Britonum.’ Et post pauca querentes adiciunt: ‘Nos mare ad barbaros, barbari ad mare repellunt. Interea oriuntur dup genera funeris. Aut enim submergimur aut iugulamur.’ Nec pro eis quicquam adiutorii habentes tristes redeunt...