Guenevere

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

This page has moved to https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/guenevere/

It is no longer being maintained here. Please visit its new location for up to date texts, images, and links.

E.H. Garrett, illustration to Francis Nimmo Greene, Legends of King Arthur and His Court (1901)

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia regum Britannie , c. 1136

Despite later developments of the story which focus, as the illustration opposite does, on the young Guenevere marrying (often reluctantly) a much older Arthur, there is very little detail about Guenevere at all in Geoffrey’s Historia (and remember that Arthur comes to the throne at the age of 15):

Finally, when he had restored the whole country to its earlier dignity, he himself married a woman called Guinevere. She was descended from a noble Roman family and had been brought up in the household of Duke Cador. She was the most beautiful woman in the entire island.

Geoffrey’s Guenevere does betray Arthur, but not with Lancelot, as the French knight has yet to appear on the scene. Instead, this is the news Arthur receives while away on his Roman campaign:

When summer came, he made ready to set out for Rome, and was already beginning to make his way through the mountains when the news was brought to him that his nephew Mordred, in whose care he had left Britain, had placed the crown upon his own head. What is more, this treacherous tyrant was living adulterously and out of wedlock with Queen Guinevere, who had broken the vows of her earlier marriage.

From Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Welsh Triads)

Geoffrey may have known of a Welsh tradition that Guenevere was faithless. She appears twice in the Welsh Triads, verses which may originally have been mnemonics for oral performance of narratives that have now been lost. Some of the Triads show the influence of later Arthurian narrative, and some survive in manuscripts dated as late as the 15th century, but it is generally agreed that the Triads also preserve some very old story material:

TRIAD 56

Arthur’s Three Great Queens:

Gwennhwyfar daughter of Cywryd Gwent,

and Gwenhwyfar daughter of Gwythyr son of Greidiawl,

and Gwenhwyfar daughter of Gogfran the Giant.TRIAD 80

Three Faithless Wives of the Island of Britain.Three daughters of Culfanawyd of Britain: Essyllt Fair-Hair (Trystan’s mistress),

and Penarwan (wife of Owain son of Urien),

and Bun, wife of Fflamddwyn.And one was more faithless than those three: Gwenhwyfar, Arthur’s wife, since she shamed a better man than any (of the others).

The image is a small view of Triad 56 (Teir prif rieni arthur ) in Welsh; you can flip electronically through the whole of the Red Book of Hergest at Oxford University’s Early Manuscripts at Oxford University project. You may also be interested in a page I have mounted for another course: see The Welsh Triads.

Image from Oxford, Jesus College MS 111, appears by permission of the Master and Fellows of Jesus College Oxford.

From La3amon’s Brut

Geoffrey was adapted into Anglo Norman by Wace, and Wace was adapted into early Middle English by La3amon in his Brut: you will find a few selections below, with translations in square brackets.La3amon is often seen as less courtly than Wace, but he does make it clear that Arthur loves Guenevere:

me imætte a sweuen; þer-uore ich ful sari æm.

Me imette þat mon me hof; uppen are halle.

þa halle ich gon bi-striden; swulc ich wolde riden.

alle þa lond þa ich ah; alle ich þer ouer sah.

and Walwain sat biuoren me; mi sweord he bar an honde.

þa com Moddred faren þere; mid unimete uolke.

he bar an his honde; ane wiax stronge.

he bigon to hewene hardliche swiðe.

and þa postes for-heou alle; þa heolden up þa halle.

Þer ich iseh Wenheuer eke; wimmonnen leofuest me.

al þere muche halle rof; mid hire honden heo to-droh.

Þa halle gon to hælden; and ich hæld to grunden.

þat mi riht ærm to-brac; þa seide Modred Haue þat.

Adun ueol þa halle; & Walwain gon to ualle.

and feol a þere eorðe his ærmes brekeen beine.

& ich igrap mi sweord leofe; mid mire leoft honde.

and smæt of Modred is hafd þat hit wond a þene ueld.

And þa quene ich al to-snaðde; mid deore mine sweorede.

and seo[ð]ðen ich heo adu[n] sette. in ane swarte putte.(13983-14002)

Longe bið æuere; þat no wene ich nauere.

þat æuere Moddred mi mæi;

wolde me biswiken. for alle mine richen.

no Wenhauer mi quene; wakien on þonke.

nulleð hit biginne; for nane weorld-monne.

Æfne þan worde forð-riht; þa andswarede þe cniht.

Ich sugge þe soð leofe king; for ich æm þin vnder-ling.

þus hafeð Modred idon; þine quene he hafeð ifon.

and þi wun-liche lond; isæt an his aere hond.

he is king & heo is que[ne]; of þine kume nis na wene.

for no weneð heo nauere to soðe; þat þu cumen aain from Rome.

Ich æm þin aen mon; & iseh þisne swike-dom.

and ich æm icumen to þe seoluen; soð þe to suggen.

Min hafued beo to wedde; þat isæid ich þe habbe.

soð buten lese; of leofen þire quene.

& of Modrede þire suster sune; hu he hafueð Brut-lond þe binume (14036-14052)

[Then Arthur, the noblest of all kings, answered, “As long as time shall last, I will never believe that my kinsman Mordred would ever betray me, not for all my kingdom; nor that Guenevere my queen would weaken in resolve; she would never do so, not for any man in the world.” And right away the knight answered these words: “Beloved king, I tell you the truth, for I am your subject: Mordred has done this. He has taken your queen, and this fair land, taken them into his own hand. He is king and she is queen; no one thinks you will return. Indeed, they do not believe that you will come again from Rome. I am your own man, and I saw this treachery, and I am come to you myself, to tell you the truth. May my head be forfeit if I have not told you the truth, with no lies, about your beloved queen, and about Mordred, your sister’s son: how he has taken Britain from you.” ]

Arthur and Guenevere in happier times, from British Library, MS Royal 14.E.iii, folio 89r. By permission of the British Library.

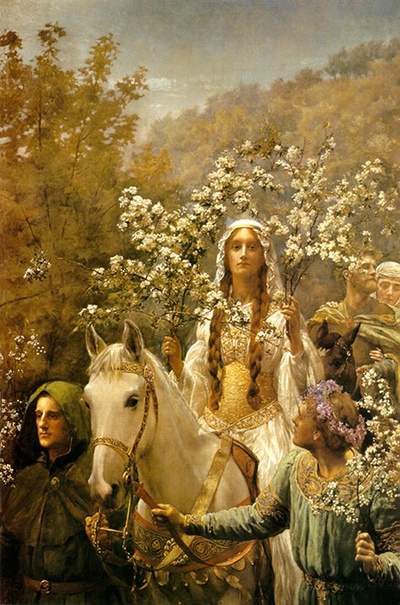

Above is Guinevere's Maying, by John Collier (1850-1934).

The image, from Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

From Chrétien de Troyes, Le Chevalier de la Charrette

It is the French writer Chrétien de Troyes who introduces the idea of the adultery between Lancelot and Guenevere, in his Chevalier de la Charrette. You can get a sense of what the poem looks like at the Charrette Project. Below is a translation of a section where Lancelot and Guenevere spend the night together:

The window is by no means low, nevertheless Lancelot passes through quickly and easily. After finding Kay asleep in his bed, he comes to that of the queen, to whom he bows in adoration, for no holy relic inspires him with such faith. The queen holds out her arms to him and embraces him, hugging him to her breast, then draws him into her bed beside her, showing him all the endearments of which she is capable, prompted by the love in her heart. The warmth of her welcome is motivated by love; and if he was very dear to her, his love for her was a hundred thousand times as great, for love in all other hearts was non-existent compared with that in his own: in his heart love was wholly rooted and so totally present that there was but a meagre supply for all other hearts.There is little sense of guilt here, though you will notice that Lancelot’s love is much greater than is Guenevere’s. By the Victorian period, Guenevere is often portrayed as a second Eve. Her sensuality is stressed in both paintings and in poetry.

From Algernon Charles Swinburne, Lancelot

Lo, between me and the light

Grows a shadow on my sight,

A soft shade to left and right,

Branched and graved as a tree.

Green the leaves that stir between,

And the buds are lithe and green,

And against it seems to lean

One in stature as the Queen

That I prayed to see.

Ah, what evil thing is this?

For she hath no lips to kiss,

And no brows of balm and bliss

Bended over me.

For between me and the shine

Grows a face that is not mine,

On each curve and tender line

And each tress drawn straight and fine

As it used to be.

THE ANGEL

This is Guenevere the Queen.

LANCELOT

For the face that comes between

Is like one that I have seen

In the days that were.

Nay, this new thing shall not be.

Is it her own face I see

Thro’ the smooth leaves of the tree,

Sad and very fair?

All the wonder that I see

Fades and flutters over me

Till I know not what things be

As I seemed to know.

But I see so fair she is,

I repent me not in this;

And to kiss her but one kiss

I would count it for my bliss

To be troubled so,

For she leans against it straight,

Leans against it all her weight,

All her shapeliness and state;

And the apples golden-great

Shine about her there.

Light creeps round her as she stands,

Round her face and round her hands,

Fainter light than dying brands

When day fills the eastern lands

And the moon is low.

And her eyes in some old dream

Woven thro’ with shade and gleam

Stare against me till I seem

To be hidden in a dream,

To be drowned in a deep stream

Of her dropping hair.

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) composed and shot a series of photographs in 1874 to illustrate Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. There are many images and related materials at the Victoria and Albert Museum page for the photographer. The images above are from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of New York; click each image to go to its information page on the Museum’s website.

Images appear in accordance with the terms for educational use published at www.metmuseum.org.

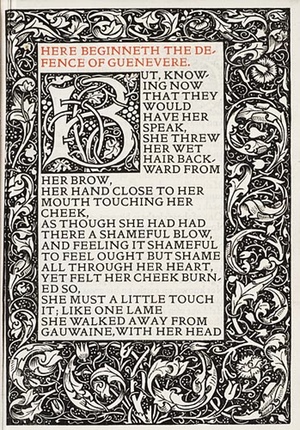

From The Defence of Guenevere, by William Morris

“Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.”

Her voice was low at first, being full of tears,

But as it cleared, it grew full loud and shrill,

Growing a windy shriek in all men’s ears,

A ringing in their startled brains, until

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

Though still she stood right up, and never shrunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

She stood, and seemed to think, and wrung her hair,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

With passionate twisting of her body there...

“I was half mad with beauty on that day,

And went without my ladies all alone,

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

“I was right joyful of that wall of stone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

“Yea right through to my heart, grown very shy

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

“A little thing just then had made me mad;

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

Sometimes, upon my beauty; if I had

“Held out my long hand up against the blue,

And, looking on the tenderly darken’d fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

“There, see you, where the soft still light yet lingers,

Round by the edges; what should I have done,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

“And startling green drawn upward by the sun?

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

“With faintest half-heard breathing sound: why there

I lose my head e’en now in doing this;

But shortly listen: In that garden fair

“Came Launcelot walking; this is true, the kiss

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

I scarce dare talk of the remember’d bliss,

“When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

“Never within a yard of my bright sleeves

Had Launcelot come before: and now so nigh!

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

“Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.”

You can read the whole poem online at the Camelot Project, and you can flip through a digital facsimile at Morris Online Edition.

That Hair

Morris and Swinburne both make much of Guenevere’s hair, using it as a symbol of her sensuality; you will see that Tennyson does the same. The illustrations below show various ways of treating Guenevere’s body at the moment of the final scene with Arthur, and in her convent life. The first two illustrations are among the many made for Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (these are from an 1898 edition, illustrated by GW. and Louis Rhead).

Two Modern Gueneveres

There is no shortage of modern retellings of Arthurian myth, and thus there are many modern views of Guenevere. Here are two:

“Lancelet, come here and sit by me,” and sitting on the edge of the bed, he stretched out his hand to his friend. “You too, sweeting — now listen to me, both. Gwenhwyfar has no child — and do you think I have not seen how you two look at each other? I spoke of this once to Gwen, but she is so modest and pious, she would not hear me. Yet now at Beltaine, when all life on this earth seems to cry out with breeding and fertility... how can I say this? There is an old saying among the Saxons, a friend is one to whom you will lend your favorite wife and your favorite sword...”

(Marion Zimmer Bradley, The Mists of Avalon, 1982)

And Launcelot and Guinevere were the most notable adulterers ever to be, for their joining was not in ignorance of the consequences nor as a result of a magical potion, but they came together from Envy and Vanity and the offspring of these: the hunger for mastery by man over woman and vice versa.

(Thomas Berger, Arthur Rex, 1978)