14th-century chalice: Walters Art Museum, Creative Commons license

Perceval and the Holy Grail

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

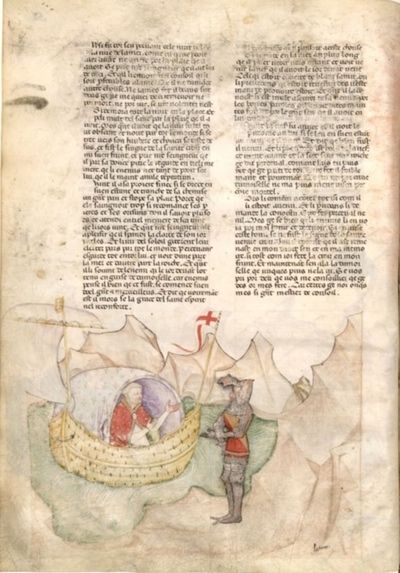

The image to the right is taken from a 15th-century French manuscript of the Vulgate cycle (also called the Lancelot-Grail cycle) of Arthurian romance; the Grail section is called the Queste del Sant Graal . In this text, while both Perceval and Galahad are (successful) participants in the Grail quest, Galahad has become a primary figure. This page traces the background of Perceval, as well as some of the other medieval narratives which concern the Grail. I have created a separate page for Galahad, as well as a page summarizing the events of the French version of the Queste.

The illustration shows the Grail Pentecost, when the Grail appears to Arthur and his knights. Click the image to visit an online facsimile of the entire manuscript.

Perceval, in his earliest appearances, is sometimes a figure of fun: an uncouth youth whom the court often mocks. For example, in the Welsh Peredur son of Efrawg, the opening of which appears to the right, the Arthurian court throws sticks at Peredur when he first appears on his ungainly horse.

The story of Perceval also suggests the Fair Unknown motif. In this excerpt from Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval , Kay makes fun of young Perceval’s desire to be a knight, but Arthur seems to recognize his quality:

“By the faith I owe the Creator, good lord king,” says the lad, “I’ll not be a knight in a hurry, unless I’m a red knight. Give me the arms of that one I met I met in front of the gate carrying off your golden cup!”The seneschal, who was one of the wounded, was angry at what he heard and said: “You’re right, my friend. Go at once and seize those arms from him, for they’re yours! It wasn’t at all foolish of you to come here for that!” Hearing this, the king was enraged and said to Kay: “You’re very wrong to mock this lad: that’s a very grave fault in a gentleman. Although the youth is naive, he may well be of good birth; for it’s a matter of upbringing, and he has learnt under a bad master. He can still turn out a worthy vassal.”

Perceval is also sometimes presented as the Holy Fool, a figure whose occasional foolishness is outweighed by his childlike nature and trust in God. The divine messenger who appears to him in the French Queste remarks that Perceval “will ever be simple,” but after this encounter an angelic voice tells Perceval that he has conquered, and will have God as his guide.

The manuscript to the left shows the heavenly messenger appearing to Perceval. This is manuscript of the French text, produced in Pavia or Milan somewhere around 1380-1385. Click the image to go to a full digital facsimile of the manuscript.

The image from Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS français 343, folio 32v, appears in accordance with the BNF terms of non-commercial use.

The divine messenger appears after Perceval has had various adventures and misadventures. The image on the right shows Perceval fighting a dragon, that he has come upon in combat with a lion. Perceval’s instinctive preference for the lion (commonly associated with Christ) indicates his innate good nature. Click the image to go to a full digital facsimile of this manuscript.

The image from Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS français 120, folio 537r, appears in accordance with the BNF terms of non-commercial use.

At his firste in-comynge,

His mere, withowtten faylynge,

495 Kyste the forhevede of the Kynge -

So nerehande he rade!

The Kyng had ferly thaa,

And up his hande gan he taa

And putt it forthir hym fraa,

500 The mouthe of the mere.

He saide, “Faire childe and free,

Stonde still besyde mee,

And tell me wythen that thou bee,

And what thou will here.”

505 Than said the fole of the filde,

“I ame myn awnn modirs childe,

Comen fro the woddes wylde

Till Arthure the dere.

Yisterday saw I knyghtis three:

510 Siche on sall thou make mee

On this mere byfor the,

Thi mete or thou schere!”

The Middle English Sir Perceval of Galles (excerpt to the left) concentrates almost exclusively on humour in the opening of the piece, as Perceval rides his mare into Arthur’s hall so that the mare “kissed the forehead of the king.”

Notice that here Perceval is called a “fool of the field.”

The text of Sir Perceval of Galles is available in its entirety online, with an introduction, notes, and glosses, as part of the TEAMS collection of Middle English texts.

The picture above is Arthur Rackham’s illustration of the Grail maiden from Alfred Pollard’s 1917 Romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table , an abridgement for children of Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur . You can see more of Rackham’s illustrations online at the Camelot Project; click here to go straight to the Artists Menu, then click on R for Rackham.

Chrétien de Troyes’ unfinished romance of Perceval includes this mysterious procession with a “graal,” an object whose shape and purpose are not entirely clear:

While they were talking of this and that, out of a room came a youth holding a white lance grasped by the middle; and he passed by between the fire and those seated on the couch. And everyone present could see the white lance with its shining head; and from the tip of the lance-head oozed a drop of blood, a crimson drop that ran down right to the lad's hand. The young man who had arrived there that night saw this marvel, but refrained from asking how this thing happened, since he remembered that warning given him by the man who knighted him and taught and instructed him to beware of talking too much. He feared that, had he asked, it would have been thought impolite; and so he did not enquire. Thereupon two other youths came, holding in their hands pure gold candlesticks inlaid with black enamel. The lads carrying the candelabras were extremely handsome. At least ten candles were burning in each candelabra.

A damsel, who came with the youths and was fair and attractive and beautifully adorned, held in both hands a grail. Once she had entered with this grail that she held, so great a radiance appeared that the candles lost their brilliance just as the stars do at the rising of the sun or moon. After her came another maiden, holding a silver carving-dish. The grail, which proceeded ahead, was of pure refined gold. And this grail was set with many kinds of precious stones, the riches and most costly in sea or earth: those stones in the grail certainly surpassed all others...

The Middle Welsh Peredur , a text whose relationship to Chrétien’s is still a matter of some debate, has a rather different version of this procession:

He saw two lads entering the hall and then leaving for a chamber; they carried a spear of incalculable size with three streams of blood running from the socket to the floor. When everyone saw the lads coming they set up a crying and a lamentation that was not easy for anyone to bear, but the man did not interrupt his conversation with Peredur – he did not explain what this meant, nor did Peredur ask him. After a short silence two girls entered bearing a large platter with a man’s head covered with blood on it, and everyone set up a crying and lamentation such that it was not easy to stay in the same house.

Notice that here what is carried in the Welsh text is a platter. The tradition which wins out is that the Grail is a cup, eventually identified as the cup of the Last Supper, and the cup that caught the blood of Christ at the Deposition from the Cross.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Damsel of the Sanct Grael, 1857. Photo © Tate London, 2012. Image appears in accordance with Tate terms for educational use.

Compare, too, Rossetti’s painting to this extract from Algernon Charles Swinburne’s 1860 poem “Lancelot.” At this point in the poem, Lancelot sees a vision of the Grail:And anon there came in a dove at a window, and in her mouth there seemed a little censer of gold. And therewithal was such a savour as all the spicery of the world had been there. And forthwithal there was upon the table all manner of meats and drinks that they could think upon.

So came in a damosel passing fair and young, and she bare a vessel of gold betwixt her hands; and thereto the king kneeled devoutly, and said his prayers, and so did all that were there.

Ah! dear Christ, this thing I see

Is too wonderful for me,

If I think indeed to be

In Thy very grace.

Clear flame shivers all about,

But the bright ark alters not,

Borne upright where angels doubt;

The blessed maiden looketh out

White, with barèd face and throat

Leaned into the dark.

On her hair's faint light and shade

A large aureole is laid,

All about the tresses weighed.

You can read the rest of this poem online at the Camelot Project; click here to go to the Authors Menu, then click on S for Swinburne.

For other visual resources, visit the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource, and the Rossetti Archive.