Arthurian Swords

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

THIS PAGE HAS MOVED TO https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/arthurian-swords/ AND IS NO LONGER BEING MAINTAINED HERE. PLEASE VISIT ITS NEW LOCATION FOR UP TO DATE CONTENT AND IMAGES

Westminster Palace sword. By permission of the British Museum.

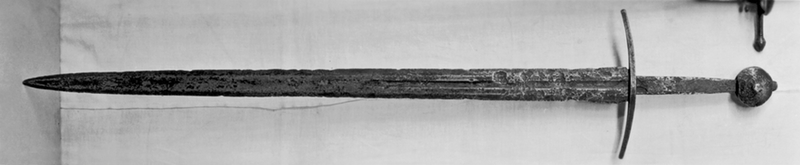

Peniarth 4, fol. 84r. By permission of the National Library of Wales.

One of the earliest references to Arthur’s weapons occurs in the Welsh prose tale of Culhwch ac Olwen (mid 11th century), when Arthur responds to Culhwch's request for a “boon” in this way:

“Chieftain,” said Arthur, “even though you do not say, you shall have the request that head and tongue name, as far as the wind dries, as far as the rain wets, as far as the sun rises, as far as the sea stretches, as far as the earth extends, excepting only my ship, my mantle, my sword Caledvwlch, my spear Rhongomynyad, my shield Wynebgwrthucher, my knife Carnwennan and my wife Gwenhwyvar.”

Click the image to the left to go to the White Book of Rhydderch (NLW MS Peniarth 4) at the National library of Wales website. The tale of Culhwch begins on folio 79v.

The reference to the spear may be what Geoffrey of Monmouth has in mind in his description of Arthur's weapons in the Historia regum Britannie (c. 1136):

Arthur himself was clothed in a breastplate worthy of so great a king, and he placed on his head a golden helmet sculpted in the likeness of a dragon. On his shoulders was his shield, called Pridwen, on which the image of the blessed Mary, mother of God, was depicted, so that she was continually called to his memory. He was girded with his sword Caliburn, the best of swords, made in the island of Avalon, and a spear called Ron adorned his right hand; this spear was long and broad, well-suited for battle.

Click the image to the right to go to NLW Peniarth 23C, a Welsh translation of the Historia. The image here shows King Arthur.

Peniarth 23c, fol. 75v. By permission of the National Library of Wales.

There is a Welsh description of Arthur’s sword, but it occurs in the Breudwyt Rhonabwy, or Dream of Rhonabwy, an early 13th-century parodic tale. Arthur is not heroic in this text, so it is difficult to determine how to take the description:

Then they heard Cadwr Earl of Cornwall being summoned, and saw him rise with Arthur’s sword in his hand, with a design of two serpents on the golden hilt; when the sword was unsheathed what was seen from the mouths of the serpents was like two flames of fire, so dreadful that it was not easy for anyone to look.

This description could suggest the decoration found on Romano-Celtic swords. To see some authetic Iron Age and Romano-British weapons, visit the British Museum:

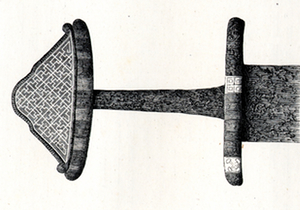

Celtic Life in Iron Age Britain is an on-line tour which includes images of weapons and related material. The Kirkburn Sword is an Iron Age sword dated 300 to 200 BC. In the Museum’s online highlights display, you can also see pictures of Romano-British objects, including the Fulham Sword and the Hod Hill Sword, both from the 1st century AD. These swords are both a bit early for Arthur’s historical period, and it is in any case quite probable that writers in the later Middle Ages had mental pictures more like the sword below (14th century) in mind.

For other images of medieval swords, search the Metropolitan Museum of New York's Collection database for arms and armor, of the Arms and Armor collection of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (the sword image below is from the Walters collection, which has made its images available via a Creative Commons license). You can also search the object database of the Royal Armouries museum in Leeds.

For much more information about swords, visit the Mediaeval Sword Resource site.

MS Royal 20 A ii, fol. 4r; by permission of the British Library.

Geoffrey’s description of Arthur’s arms participates in a long epic tradition, in which the arms of the hero are described before a significant battle. The continued importance of that tradition can be seen, for example, in the long description of the arming of Sir Gawain in the 14th-century Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The excerpt below is the description of Gawain’s shield, with its symbolic pentangle device.

THEN þay schewed hym þe schelde, þat was of schyr goulez

Wyth þe pentangel depaynt of pure golde hwez.

He braydez hit by þe bauderyk, aboute þe hals kestes,

Þat bisemed þe segge semlyly fayre.

And quy þe pentangel apendez to þat prynce noble

I am in tent yow to telle, þof tary hyt me schulde:

Hit is a syngne þat Salamon set sumquyle

In bytoknyng of trawþe, bi tytle þat hit habbez,For hit is a figure þat haldez fyue poyntez,

And vche lyne vmbelappez and loukez in oþer,

And ayquere hit is endelez; and Englych hit callen

Oueral, as I here, þe endeles knot.

Forþy hit acordez to þis kny3t and to his cler armez,

For ay faythful in fyue and sere fyue syþez

Gawan watz for gode knawen, and as golde pured,

Voyded of vche vylany, wyth vertuez ennourned

in mote;

Forþy þe pentangel nwe

He ber in schelde and cote,

As tulk of tale most trwe

And gentylest kny3t of lote.

The image on the left is taken from London, British Library Royal 20 A ii, a 14th-century copy of the Chronicles of England. It shows King Arthur with the Virgin Mary painted on his shield. Click on the thumbnail to go to other pictures from this manuscript.

Gawain’s arms are described, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in terms of their reflection of Gawain’s high moral worth: he bears the pentangle knot on his shield because he is “Voyded of vche vylany, wyth vertuez ennourned/ in mote” (Devoid of every vice, and adorned with all virtues).

Gawain’s arms are described, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in terms of their reflection of Gawain’s high moral worth: he bears the pentangle knot on his shield because he is “Voyded of vche vylany, wyth vertuez ennourned/ in mote” (Devoid of every vice, and adorned with all virtues).

Arthur’s own swords in Malory, as discussed below, are associated more with his right to rule than with any particular moral qualities, but there are swords in Malory which reveal something about the worth of their bearer. The first is the sword born by the maiden in the story of Balin and Balan, in Book II:

Than she lette hir mantell falle that was rychely furred, and than was she gurde with a noble swerde, wherof the kynge had mervayle and seyde, “Damesel, for what cause are ye gurte with that swerde? Hit besemyth you nought.” “Now shall I telle you,” seyde the damesell. “Thys swerde that I am gurte withall doth me grete sorow and comberaunce, for I may nat be delyverde of thys swerde but by a knyght, and he muste be a passynge good many of hys hondys and of hys dedis, and withoute velony other trechory and withoute treson. And if I may fynde such a knyght that hath all thes vertues he may draw oute thys swerde oute of the sheethe..... [Balin succeeds in drawing the sword and proving his worth, but when he refuses to give it back, it becomes a symbol of his fate:] ... “Well,” seyde the damesell, “ye ar nat wyse to kepe the swerde fro me, for ye shall sle with that swerde the beste frende that ye have and the man that ye moste love in the worlde, and that swerde shall be your destruccion.”

The image above is one of Sir William Russell Flint’s illustrations to a 1911 edition of Malory’s Morte, and appears by permission of the estate of Sir William Russell Flint

MS Royal 14 E iii, fol. 91r. By pemission of the British Library.

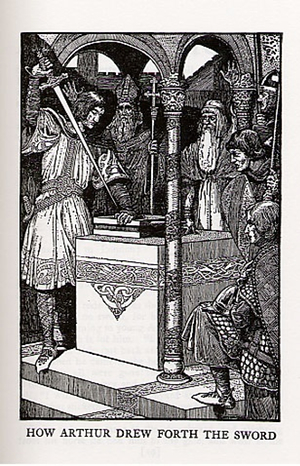

Like Balin’s sword, Galahad’s sword reveals its bearer’s worth, and it is associated with fate, though more positively. While Balin’s sword becomes his doom, Galahad’s sword is part of his destiny in the Grail quest, and one of the signs that he will succeed. The first passage below is the description of the sword in Malory’s source, the French Queste del Sant Graal. The image to the left is taken from an early 14th-century copy of the text, now is the British Library (click the thumbnail to see many more pictures from this manuscript). The illustration shows Galahad drawing the sword from the marble block in front of Arthur and his court.

The king and his barons went down at once to see this marvel. When they came to the river bank, they found the great stone lying now by the water’s edge. Held fast in its red marble was a sword, superb in its beauty, with a pommel carved from a precious stone cunningly inlaid with letters of gold. The barons examined the inscription which read: NONE SHALL TAKE ME HENCE BUT HE AT WHOSE SIDE I AM TO HANG. AND HE SHALL BE THE BEST KNIGHT IN THE WORLD.

The next passage below is Malory’s version of the story:

Than the kynge seyde, “I woll se that mervayle.” So all the knyghtes wente with hym. And whan they cam unto the ryver they founde there a stone fletynge, as hit were of rede marbyll, and therin stake a fayre ryche swerde, and the pomell thereof was of precious stonys wrought with lettirs of golde subtyle. Than the barownes redde the lettirs whych seyde in thys wyse: “NEVER SHALL MAN TAKE ME HENSE BUT ONLY HE BY WHOS SYDE I OUGHT TO HONGE AND HE SHALL BE THE BESTE KNYGHT OF THE WORLDE.”

There are two different swords associated with Arthur himself in Malory. The first is the sword in the stone (about which more below), and the second — the one that he receives from the Lady of the Lake as in the picture to the right — is the sword that is traditionally called Excalibur (though there is an earlier reference to the sword by name in Malory: a slip, perhaps?) Below you will find excerpts from Malory and his sources, telling the stories of these two swords.

There are two different swords associated with Arthur himself in Malory. The first is the sword in the stone (about which more below), and the second — the one that he receives from the Lady of the Lake as in the picture to the right — is the sword that is traditionally called Excalibur (though there is an earlier reference to the sword by name in Malory: a slip, perhaps?) Below you will find excerpts from Malory and his sources, telling the stories of these two swords.

The image on the right is one of Daniel Maclise’s illustrations to the 1857 edition of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. The two images below are among Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for the 1893-94 Dent edition of Malory’s Morte. We have copies of all of these books in Rare Books and Special Collections.

Excalibur comes to Arthur from the Lady of the Lake:

So they rode tyll they com to a laake that was a fayre watir and brode. And in the myddis Arthure was ware of an arme clothed in whyght samyte, that held a fayre swerde in that honde. “Lo,” seyde Merlion, “yonder ys the swerde that I spoke off.” So with that they saw a damesell goynge uppon the laake. “What damoysel is that?” said Arthur. “That is the Lady of the Lake,” seyde Merlion. “There ys a grete roche, and therein ys as fayre a paleyce as ony on erthe, and rychely besayne. And thys damesel woll com to you anone, and than speke ye fayre to hir, that she may gyff you that swerde.”.... So kynge Arthure and Merlion alyght and tyed their horsis unto two treys; and so they wente into the barge. And whan they come to the swerde that the honde hylde, than kynge Arthure toke hit up by the hondils and bare hit with hym, and the arme and the honde wente undir the watir.

Malory gets his account of Bedivere from the French Mort le Roi Artu. Compare the two accounts below:

When Girflet saw that he had to do it, he went back to where the sword was. He picked it up and began to gaze at it and to have regrets about it, saying: “You splendid and beautiful sword, what a great pity it is for you that you will not fall into the hands of some noble man!” Then he hurled it into the lake as deep and as far from him as he could, and as it fell near the water, he saw a hand come out of the lake which revealed itself up to the elbow, but he saw nothing of the body to which it belonged. The hand seized the sword by the hilt and brandished it in the air three or four times.

Than sir Bedwere departed and wente to the swerde and lyghtly toke hit up, and so he wente unto the watirs syde. And there he bounde the gyrdyll aboute the hyltis, and threw the swerde as farre into the watir as he myght. And there cam an arme and an honde above the watir, and toke hit and cleyght hit, and shoke hit thryse and braunndysshed, and than vanysshed with the swerde into the watir. (II.517)

Soo in the grettest chirch of London — whether it were Powlis or not the Frensshe booke maketh no mencyon — alle the estates were longe or day in the chirche for to praye. And whan matyns and the first masse was done there was sene in the chircheyard ayenst the hyhe aulter a grete stone four square, lyke unto a marbel stone, and in myddes therof was lyke an anvylde of stele a foot on hyghe, and theryn stack a fayre swerd naked by the poynt, and letters there were wryten in gold about the swerd that saiden thus: “Whos pulleth oute this swerd of this stone and anvyld is rightwys kynge borne of all Englond.”

Arthur does indeed draw the sword and prove his birthright in Malory, but he later tells Merlin, before the meeting with the Lady of the Lake, that he has no sword — so this sword in not Excalibur. The dramatic moment in which he draws the sword has been represented over and over in words and illustrations; below is part of the scene from T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone (1938):

Arthur does indeed draw the sword and prove his birthright in Malory, but he later tells Merlin, before the meeting with the Lady of the Lake, that he has no sword — so this sword in not Excalibur. The dramatic moment in which he draws the sword has been represented over and over in words and illustrations; below is part of the scene from T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone (1938):

He turned his mount and cantered off the street. There was a quiet churchyard at the end of it, with a kind of square in front of the church door. In the middle of the square there was a heavy stone with an anvil on it, and a fine new sword was stuck through the anvil. “Well,” said the Wart, “I suppose it is some sort of war memorial, but it will have to do. I am sure nobody would grudge Kay a war memorial, if they knew his desperate straits.” He tied the reins round a post of the lych-gate, strode up the gravel path, and took hold of the sword. “Come sword,” he said. “I must cry your mercy and take you for a better cause.” “This is extraordinary," said the Wart. “I feel stronger when I have hold of this sword, and I notice everything much more clearly. Look at the beautiful gargoyles of the church and of the monastery which it belongs to. See how splendidly all the famous banners in the aisle are waving. How nobly that yew holds up the red flakes of its timbers to worship God. How clean the snow is. I can smell something like fetherfew and sweet briar — and is it music that I hear?”

If you would like your own Excalibur, there are many places on the web to get one. I include a few links below.

Casiberia sells many medieval-style swords

Ritterlader features medieval weapons and armous

Museum Replicas has a latex version of Excalibur

You can learn historical sword-fighting styles here in Vancouver at Academie Duello