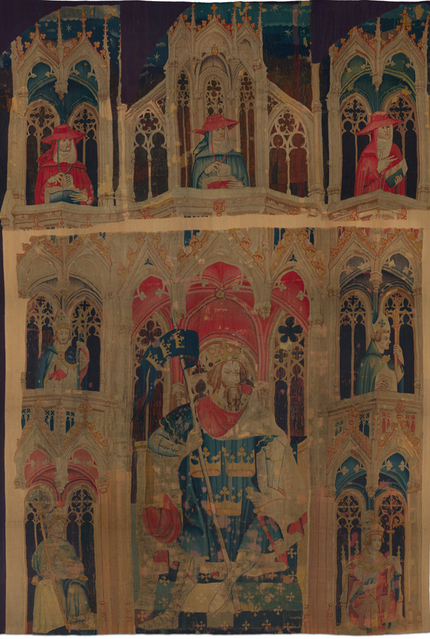

Detail from BL Royal 18 D ii, fol. 30v, by permission of the British Library. Click the thumbnail to see more about this MS.

King Arthur and Fortune

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

Early in the Historia regum Britannie, Leir berates Fortune as he muses on the contrast between his current wretchedness and his past glories:

Indeed, the memory of the time when, attended by so many hundred thousand fighting-men, I used to batter down the walls of cities and to lay waste the provinces of my enemies saddens me more than the calamity of my own present distress, although it has encouraged those who once grovelled beneath my feet to abandon me in my weakness. Oh, spiteful Fortune! Will the moment never come when I can take vengeance upon those who have deserted me in my final poverty?

A major source for the medieval view of Fortune is Consolatio Philosophiae, by Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, a noble Roman who was executed in 524. The Consolation is set in prison, as the speaker, awaiting death, laments the change in his fortunes. Lady Philosophy appears to him, and tells him that a wise men does not put his faith in Fortune, even when she is helping him: it is the nature of Fortune to change. Here is Philosophy’s description of the ways of Fortune:

A major source for the medieval view of Fortune is Consolatio Philosophiae, by Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, a noble Roman who was executed in 524. The Consolation is set in prison, as the speaker, awaiting death, laments the change in his fortunes. Lady Philosophy appears to him, and tells him that a wise men does not put his faith in Fortune, even when she is helping him: it is the nature of Fortune to change. Here is Philosophy’s description of the ways of Fortune:

You have given yourself over to Fortune’s rule, and you must bow yourself to your mistress’s ways. Are you trying to stay the force of her turning wheel? Ah! dull-witted mortal, if Fortune begin to stay still, she is no longer Fortune.

As thus she turns her wheel of chance with haughty hand, and presses on like the surge of Euripus’s tides, fortune now tramples fiercely on a fearsome king, and now deceives no less a conquered man by raising from the ground his humbled face. She hears no wretch’s cry, she heeds no tears, but wantonly she mocks the sorrow which her cruelty has made. This is her sport: thus she proves her power; if in the selfsame hour one man is raised to happiness, and cast down in despair, ’tis thus she shews her might.

You can read the whole poem in translation here or here.

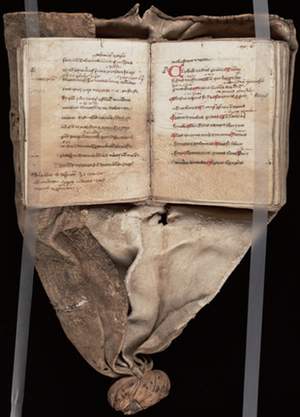

The image to the rights is a 15th-century “girdle book” copy of the Consolatio, probably from England. Girdle books were small copies of books with bindings that allowed them to be tucked into a belt. Click the image to read more about this copy, Beinecke MS 84. The image appears in accordance with the terms of use of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Philosophy’s Fortuna can govern both kings and peasants, but later medieval fortune narratives seem particularly fascinated with the fall of the great. An example of this fascination is the Middle English poet John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes. Click here to see a manuscript of this poem at the University of Victoria. Lydgate based his work on Giovanni Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium (On the fall of famous men).

By the time of the Alliterative and Stanzaic Morte Arthure, discussed further below, dreams of negative fortune include the familiar iconography of Fortuna and her wheel. But even before Fortune and her wheel are explicitly invoked, prophetic dreams often include a fall from great height. Arthur’s dream of the dragon and bear in Geoffrey’s Historia is one example (and it recurs in, for example, the Alliterative Morte Arthure and in Malory’s Morte). Another is the dream that Arthur has after his victory over Lucius in La3amon’s Brut, an early 13th-century chronicle version of Geoffrey’s Historia which also drew on the adaptation made by the Anglo-Norman poet Wace. This particular dream is apparently La3amon’s invention, however.

The extract that follows offers the Middle English on the left and a translation on the right. Because of concerns about browser fonts, I have had to change some of the letters to modern equivalents, so that thorn is represented by th, and eth by d or th. The extract begins at line 13982.

Toniht a mine slepe, ther ich laei on bure,

me imaette a sweuen; theruoure ich ful sari aem.

Me imette that mon me hof uppen are halle;

Tha halle ich gon bistriden swulc ich wolde riden;

alle tha lond tha ich ah alle ich there ouer sah,

and Walwain sat biuoren me; mi sweord he bar an honde.

Tha com Moddred daren there mid unimete uolke;

he bar an his honde ane wiax stronge.

He bigon to hewene hardliche swithe

and tha postes forheou alle tha heolden up tha halle.

Ther ich iseh Wehneuer eke, wimmonnen leofest me;

al there muche halle rod mid hire honden heo todroh.

Tha halle gon to haelden and ich haeld to grunden

that mi riht aerm tobrac. Tha seide Modred Haue that!

adun ueol tha halle, and Walwain gon to ualle

and feol a there eorthe; his aermes brekeen beine.

And ich igrap mi sweord leofe mid mire leoft honde,

and smaet of Modred is hafd that hit wond a thene ueld.

And tha quene ich al tosnadde mid deore mine sweorede;

and seothen ich heo adun sette in ane swarte putte.

Tonight in my sleep, as I lay in my chamber,

I dreamed a dream; I am very uneasy from it.

I dreamed that I had been put high up on a hall:

I bestrode the hall as if I were riding.

All the land that belongs to me I looked over from there,

and Gawain sat before me, bearing my sword in his hand.

Then Modred came marching there with an enormous host;

he bore a stout battleaxe in his hand.

He began to hew very strongly

and he cut through all the posts that held up the hall.

There I also saw Guenevere, the dearest of women to me;

she pulled down the whole roof of that great hall with her hands.

The hall began to fall, and I fell to the ground

so that my right arm broke. Then Modred said Have that!

The hall fell down, and Gawain began to fall

and fell to the earth; his arms were broken.

And I gripped my beloved sword in my left hand,

and smote off Modred's head, so that it fell to the ground.

And I cut the queen all to pieces with my dear sword;

and then I thrust her down into a dark pit.

“How shal we fare,” quod the freke, “that fonden to fight,

And thus defoulen the folke on fele kinges londes,

And riches over reymes withouten eny right,

Wynnen worshipp in werre thorgh wightnesse of hondes?”

“Your King is to covetous, I warne the sir knight.

May no man stry him with strenght while his whele stondes.

Whan he is in his magesté, moost in his might,

He shal light ful lowe on the sesondes.

And this chivalrous Kinge chef shall a chaunce:

Falsely Fortune in fight,

That wonderfull wheelwryght,

Shall make lordes to light -

Take witnesse by Fraunce.”

(The Awntyrs off Arthure, 261-73; you can read the whole text online by clicking here)

The image to the left from BL MS Harley 4376, fol. 231r, showing Alexander the Great on Fortune’s Wheel, appears by permission of the British Library. Click the thumbnail to see more about this manuscript.

The association of Arthur’s fall with Fortune and her wheel is developed into a prophetic dream in the 13th-century French prose La Mort le Roi Artu, a text which was adapted into English in the 14th century as the Stanzaic Morte Arthure. Compare these dreams:

When Arthur had fallen asleep, he dreamt that a lady came before him, the most beautiful he had ever seen in the world, who lifted him up from the ground and took him up into the highest mountain he had ever seen. There she placed him on a wheel, on which there were seats, some rising and some falling. The king looked to see at which part of the wheel he was sitting, and saw he was at the highest point.

The lady asked him, “Arthur, where are you?”

“My lady,” he replied, “I am on a high wheel, but I do not know what kind of a wheel it is.”

“It is the wheel of Fortune,” she replied. Then she asked him, “Arthur, what can you see?”

“My lady, I think I can see the whole world.”

“That is true,” she said, “you can see it, and there is very little of which you have not been lord up till now. Of all the circle you can see you have been the most powerful king there ever was. But such is earthly pride that no one is seated so high that he can avoid having to fall from power in the world.”

Then she took him and pushed him to the ground so roughly that King Arthur felt that he had broken all his bones in the fall and had lost the use of his body and limbs.

At night when Arthur was brought in bed

(He sholde have batail upon the morrow),

In stronge swevenes he was bestedde,

That many a man that day sholde have sorrow,

Him thought he sat in gold all cledde,

As he was comely king with crown,

Upon a wheel that full wide spredde,

And all his knightes to him boun.

The wheel was ferly rich and round;

In world was never none half so high;

Thereon he sat richly crowned,

With may a besaunt, brooch, and bee;

He looked down upon the ground;

A black water there under him he see,

With dragons fele there lay unbound,

That no man durst them nighe nigh.

He was wonder ferde to fall

Among the fendes there that fought.

The wheel over-turned there with-all

And everich by a limm him caught.

The king gan loude cry and call,

As marred man of wit unsaught;

His chamberlains waked him there with-all,

And wodely out of his sleep he raught.(Stanzaic Morte Arthure, 3168-91; you can read the whole poem online by clicking here)

Arthur’s dream in the Alliterative Morte Arthure puts kings on the wheel, and Arthur’s philosopher tells him that these were famous conquerors: he names them as Alexander, Hector, Julius Caesar, Judas Maccabeus, Joshua, David, Charlemagne, and Godfrey de Bouillon; these are 8 of the so-called Nine Worthies. Arthur is the ninth (though he is chronologically earlier than either Charlemagne or Godfrey, of course). The motif of the Nine Worthies derives from an early 14th-century French poem called the Voeux du Paon (Vows of the Peacock). There are 3 classical heroes; 3 biblical heroes; and 3 Christian heroes.

The Cloisters Collection in New York includes part of a tapestry which represents Arthur among the Worthies; click the thumbnail to the left to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art website description of the Nine Worthies Tapestries.