John Gower

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

THIS PAGE IS NO LONGER BEING MAINTAINED: FOR A CORRECTED, UPDATED, AND EXPANDED VERSION, PLEASE VISIT ITS NEW HOME AT https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/john-gower/

G. C. Macaulay edited the poem from the Glasgow Hunterian manuscript: his edition is below, along with my own rhyming translation; do note that the translation is not meant to act as a crib, but rather sometimes sacrifices literal translation in order to give an impression of the original’s effect.

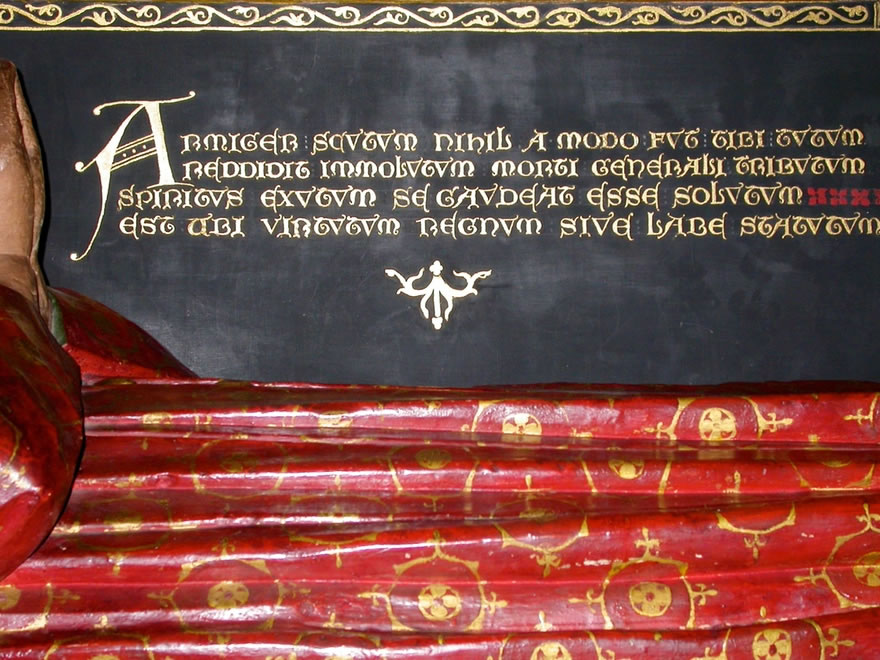

Armigeri scutum nichil ammodo fert sibi tutum

Reddidit immo lutum mortu generale tributum

Spiritus exutum se gaudeat esse solutum

Est vbi virtutum regnum sine labe statutumHenceforth the shield no shelter yields to th’arméd one.

Instead the clay grants death his day, the tribute done.

The naked soul rejoices all in its release:

In virtue’s realm it’s ’stablishèd, never to cease.

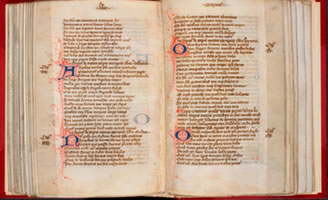

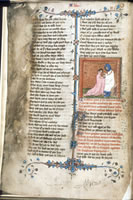

The image above from Glasgow University Library, MS Hunter 59, appears by permission of Glasgow University Library. Click the image to go to a larger version on the GUL site.

There is an ever-increasing number of images from Gower manuscripts available online. The list of links below will grow as I have more time to fill it in.

The thumbnails below are, reading left to right, from Osborn Fa1 (source: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, in accordance with their Copyright and Permissions policy), and Royal 18 C xxii, Harley 7184, Harley 3490, and Egerton 1991 (all by permission of the British Library). You can click on these to go to the library websites and see larger images. You can also click on the thumbnails in the table below, and on the shelfmark links.

London, The British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

Thumbnails of Bl Harley 3869 and BL Harley 6291 appear by permission of the British Library.

This catalogue contains images from

Egerton 1991, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Harley 3490, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Harley 3869, a manuscript containing the Confessio Amantis and the Traitié pour essampler les amantz marietz

Harley 6291, a manuscript of the Vox clamantis and Cronica tripertita

Harley 7184, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Royal 18 C xxii, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Stowe 950, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

You will find small images after the catalogue descriptions. You can click on these to get much larger images.

This database brings together images of manuscripts from many institutions. You can view images in small, medium, or large sizes. It includes the following Gower manuscripts:

Columbia Plimpton 265, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

San Marino Huntington EL 26 A 17, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

San Marino Huntington HM 150, a manuscript of the Vox Clamantis

This catalogue includes images from

Morgan M.125, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Morgan M.126, a heavily-illustrated manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Morgan M.690, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

The Bodleian Library has made thousands of images from manuscripts in its collection available online through LUNA, a system that allows you to create workspaces and zoom images. The database includes images from:

Bodley 294, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Bodley 693, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Bodley 902, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Fairfax 3, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Laud Misc. 609, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

Laud Misc. 719, a manuscript of the Vox Clamantis

Lyell 31, a manuscript of the Confessio Amantis

O reuerend Chaucere, rose of rethoris all,

As in oure tong ane flour imperiall,

That raise in Britane ewir, quho redis rycht,

Thou beris of makaris the tryumph riall;

Thy fresch anamalit termes celicall

This mater coud illumynit haue full brycht:

Was thou noucht of oure Inglisch all the lycht,

Surmounting ewiry tong terrestriall,

Alls fer as Mayes morow dois mydnycht?O morall Gower, and Ludgate laureate,

Your sugurit lippis and tongis aureate,

Bene to oure eris cause of grete delyte;

Your angel mouthis most mellifluate

Our rude langage has clere illumynate,

And faire our-gilt oure speche, that imperfyte

Stude, or your goldyn pennis schupe to wryte;

This Ile before was bare, and desolate

Off rethorike, or lusty fresch endyte.

These three still appear together in this 1614 poem by Thomas Freeman:

Pitty ô pitty, death had power

Ouer Chaucer, Lidgate, Gower:

They that equal'd all the Sages

Of these, their owne, of former Ages,

And did their learned Lights aduance

In times of darkest ignorance...

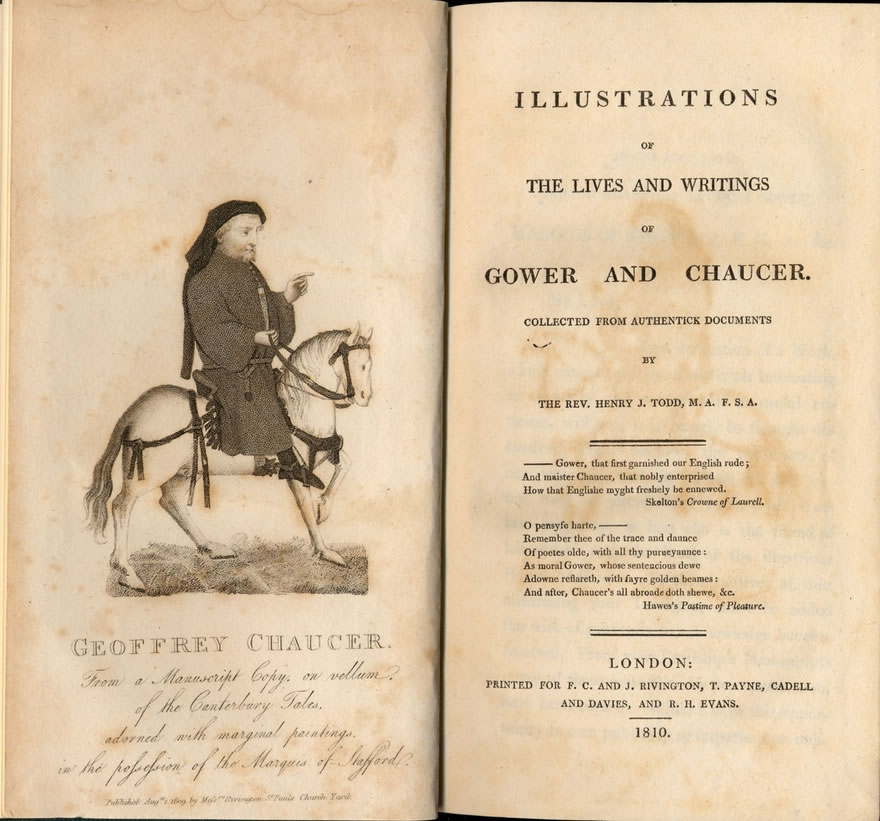

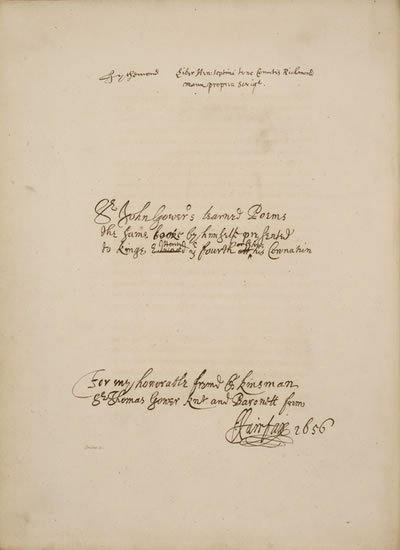

By this point Gower was relying on a combination of antiquarian interest and snob-appeal; it happened that the noble family of Gower believed themselves (erroneously) to be descended from John Gower the poet, and Todd dedicates his Illustrations (above) to George Granville Leveson Gower, Marquis of Stafford. A few years later, in 1818, George Granville Leveson-Gower, Earl Gower and later 2nd Duke of Sutherland, edited a manuscript in the family’s possession, the Trentham Manuscript (now London, British Library Additional MS 59495) of Gower’s French Balades, for the aristocratic Roxburghe Club. The illustration to the right shows the reproduction of ownership signatures which suggest that the book belonged to Henry VII and recording the transmission of the manuscript to the Gower family in 1656, and the title page of the work; the latter, you will notice, features the names of both Gower the poet and Gower the earl.

By this point Gower was relying on a combination of antiquarian interest and snob-appeal; it happened that the noble family of Gower believed themselves (erroneously) to be descended from John Gower the poet, and Todd dedicates his Illustrations (above) to George Granville Leveson Gower, Marquis of Stafford. A few years later, in 1818, George Granville Leveson-Gower, Earl Gower and later 2nd Duke of Sutherland, edited a manuscript in the family’s possession, the Trentham Manuscript (now London, British Library Additional MS 59495) of Gower’s French Balades, for the aristocratic Roxburghe Club. The illustration to the right shows the reproduction of ownership signatures which suggest that the book belonged to Henry VII and recording the transmission of the manuscript to the Gower family in 1656, and the title page of the work; the latter, you will notice, features the names of both Gower the poet and Gower the earl.

The Roxburghe Club also printed an edition of the Vox Clamantis in 1850, and then in 1857, Reinhold Pauli published his edition of the Confessio Amantis (the title page is to the right).

Pauli’s edition was a beautiful book, but its text was suspect and its design, while visually appealing, was a mixture of styles, and not particularly readable. The woodcut initials and decorations are based on 15th- and 16th-century designs, while the main font is an 18th-century style, one that was often used, by the Press that printed this edition, for its gift book offerings.

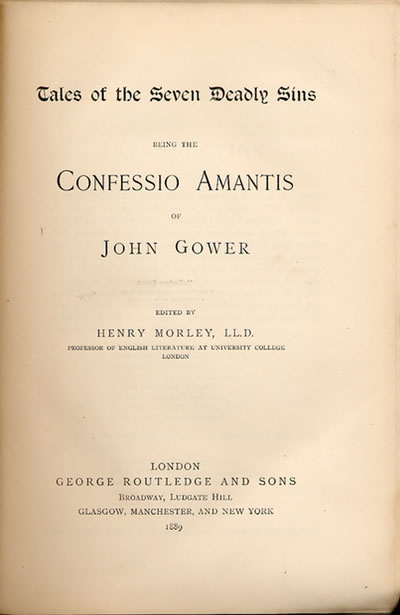

The Cinkante Balades were re-edited in 1886, and in 1889, Henry Morley produced a modernized version of the Confessio, under the title Tales of the Seven Deadly Sins. He omitted the tale of Canace and Machaire because, as he notes in the Table of Contents, “Gower against his own habitual good sense has by some aberration of mind here made his Confessor tolerant of incest.”

The first complete edition of all of Gower’s works was edited by G. C. Macaulay and published by Oxford’s Clarendon Press in 4 volumes, from 1899-1902. This is still the only complete scholarly edition, although the TEAMS Middle English text series, a series devoted to making available student editions of important but less readily available medieval texts, now includes several Gower volumes. They are freely available online:

The French Balades (with translations)

The Minor Latin Works (with translations)

There is also a new edition, with verse translation, of the Cronica tripertita and the first part (the Visio) of the Vox clamantis: see David R. Carlson and A. G. Rigg, John Gower: Poems on Contemporary Events (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2011).