Copyright © 2006 by Ronald Fedoruk

Copyright © 2006 by Ronald Fedoruk

![]() first a story

first a story

![]() the war on the pond

the war on the pond

![]() coming in from the cold

coming in from the cold

![]() the stanley cup is made of silver

the stanley cup is made of silver

![]() le poêle

le poêle

![]() bibliography

bibliography

Copyright © 2006, 2007 by Ronald Fedoruk

first a story

The winters of my childhood were long, long seasons. We lived in three places --- the school, the church and the skating-rink --- but our real life was on the skating-rink. Real battles were won on the skating-rink. Real strength appeared on the skating-rink. The real leaders showed themselves on the skating-rink...

Roch Carrier is now Canada's National Librarian, but when he chose to articulate the classic French/English cultural dichotomy, he did so in a children's story called The Hockey Sweater. This was later made into a film called The Sweater. A Quebecois boy idolizes the great Montreal Canadiens hockey team, and wears the team sweater whenever he plays. One winter, by mistake, he is given a Toronto Maple Leafs sweater, and he has to come to terms with playing in the uniform of his hated rival. Canadian archetypes are often very successfully expressed in hockey terms. Carrier's gentle story is a reminder that when political debate can sometimes be quite impassioned, it is helpful to be able to discuss our differences using a metaphor most of us understand, whether the story is told in French or in English. Not quite so gentle is Rick Salutin's 1977 play Les Canadiens. Salutin says in the introduction, "Hockey is our only universal cultural symbol." Teams become cultural icons, the arenas become shrines and the best players become national heroes. As Salutin writes:

Dieux du Forum,

Forum Gods!

Oh you, gloire à toi, Maurice.

Oh Rocket, aux pieds longs,

Tu es le centre de la passion

Qui régénère notre nation,

And you showed us the way and a light and a life.

Oh you,

Nous vous aimons et admirons!

And yet Maurice, you are the one,

Rocket, tu es le plus grand,

Parce que tu es le centre et le centre est Québécois,

Because you are the centre and the centre is Québécois,

Parce que tu es le centre et le centre est Québécois!

The recently released biopic Maurice Richard, centres on the rioting in Montreal of 1955 when the legendary Canadien was suspended for the the last three games of the season, and more importantly, for the playoffs. Richard may have tried to protest that he was "just a hockey player", but in saying this, the Rocket does not adequately recognize his cultural importance. If this were true and if hockey be just a game, then no one would be making an $8 million movie about his suspension fifty years after it occurred. François Black points out that television likely made Richard's suspension more important than it otherwise would have been, but nonetheless, numerous commentators have described this event as the opening salvo in a separatist movement that very much continues to this day.

http://radio-canada.ca/sports/hockey/2005/11/23/005-RocketFilm.shtml

Carrier is correct, real leaders do reveal themselves on the skating rink. But the real debate often happens just off the ice. Hockey, played outdoors in the depths of a Canadian winter, can be a chilly sport. So, in order to avoid frostbite and hypothermia, most outdoor rinks have a heated shack nearby. Between periods we gather in the shack around a hot stove to thaw our frozen bits and share stories, short and tall. The skate shack and its hot stove fulfil the same function as the campfire. The combined stories elevate hockey beyond being just a game. It has become a national institution, surrounded by a massive accumulation of lore, mythology, and tradition. Defining Canadian nationhood is complex; stories are wildly diverse, sometimes contradictory, often incomprehensible. In the midst of this confusion, hockey lore is a widely accessible body of knowledge, comprising stories that are understood and can generate discussion across a wide spectrum of the population. As the stories are communicated to increasing numbers of people, the game acquires more importance in defining what it means to be Canadian.

the hotstove the war on the pond

the hotstove the war on the pond

.

In September of 1972, a young Stage Manager's first job took him on tour with a ballet company; a ten week escapade through Eastern Ontario and much of Québec. So it was that he found himself deep in the Gaspésie during a defining moment in Canadian identity; the winning goal in the 1972 Canada-USSR hockey series. On any normal Saturday night the tiny lobby of the tiny Hotel Victoria in the even tinier town of La Pocatiére, was the place to come to watch the game. The afternoon of September 28 was far from normal, and the Victoria was packed with people; all but one of them Francophone. The crowd was not hostile to the young Manitoban, not at all, but the reserve was palpable. Only two years earlier the October Crisis, one of the most serious events in Canadian history, had created an obvious tension between French and English speaking Canadians, and an Anglophone in Québec was often viewed with some suspicion. In that hotel on that afternoon, he felt very much the outsider. One goal changed all that. There were only 34 seconds left in the game when Montreal's Yvan Cornoyer passed the puck to Toronto's Paul Henderson and, suddenly, it no longer mattered, being the only Anglais in the room. What mattered was that a Manitoban loved hockey the way these Québecois loved hockey. When the winning goal was scored, the whole room celebrated together because they had all witnessed, participated in, a significant, exciting Canadian story. It was important for all Canadians to be able to share that moment.

http://www.russianrocket.de/History/hauptteil_history.html

Prior to the Summit Series, professional teams of North America and Western Europe were not allowed to compete with the amateur players of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Though there was always a good deal of discussion about what constituted an amateur, Canadian rosters were usually filled by players who had not yet turned professional. International hockey was usually predictable and usually favoured the more experienced and intensively trained Soviet bloc teams. Canadians had always claimed that we were being beaten at our own game because we were not using our best players. Were we to ice a team of National Hockey League professionals, there would be a remarkably different outcome. Suddenly in September 1972, our claim was put to the test. The resulting series changed the face of hockey, and in the process, established a new sort of international diplomacy.

Marshall McLuhan in War and Peace in the Global Village refers to the handshake as an artifact of War; a formalized means of deflecting or controlling hostile emotions. To illustrate his point he uses a photograph from the final game of the 1953 Stanley Cup Championship where the Montréal Canadiens defeated the Boston Bruins. Maurice Richard, bloody from an earlier head injury, shakes hands with an equally battered Jim Henry, while similar congratulations occur among other players all over the ice.

McLuhan's observation is even more applicable today. By 2002, the post game handshake has become even more stylized, with the Canadian and Czech Olympic teams lined up to to greet each member of the opposition. Rather than the disorganized melee of handshaking that occured a half century earlier, today's players are much more systematic, even rehearsed in the mandatory obsequy. The change is a result of the passage of time, but also a requirement of the increased metaphoric role that hockey has assumed. As the game becomes more important, its form becomes more prescribed. This is especially so in international competition.

http://www.olsonboys.org/galleries/olympics/can-cze/pages/can-cze-handshake.htm

During the cold war, military strength reached such a level that neither of the potential combatants dared to attack. Just prior to 1972, it was estimated that Soviet arsenals had enough arms to kill every American citizen 87 times over. The United States had enough firepower to kill every Soviet citizen 149 times. To their credit, and to our immense relief, the Americans realized that this advantage would not actually make them a winner. There was no practical way to settle the question of which was the mightier military power. Canadians, ever the peacekeeper nation, intervened in this standoff in a manner that recalls medieval chivalry. Soviet Premier Alexai Kosygin had demonstrated his country's willingness to engage with Western countries, and Pierre Trudeau was seen as a sympathetic ear. Kosygin visited Canada in the fall of 1971, and at some point, the two leaders had agreed that a hockey series would be a good idea. By sending a designated champion into battle, a statement could be made without endangering the existence of the entire nation. It is worth noting that while the major politcal combatants were the USA and USSR, the champions chosen to represent the west in this battle were Canadian, thus adding one more layer of insulation to the superpowers in case it all went sideways. The stakes were very high indeed. The series became a metaphor for the differences in lifestyles, beliefs and politics experienced in the "free world" and the "iron curtain countries". International teams were clearly seen as cultural ambassadors, an extension of our national persona. As early as 1958, an article in The Hockey News quotes former Prime Minister Lester Pearson as saying "sports teams sent abroad, to Russia for instance, could do a lot of good, but they could also do a lot of harm." Canadian Politicians of all stripes recognized the importance of the games and scrambled to be part of the action, as did Soviet leaders.

With so much at stake, we were not allowed to lose, as underlined by at least two incidents that occurred after the Soviet team proved itself to be much better than anticipated. After its loss in Game #4, the team was booed by fans, an indication of how seriously Canadians took the series. And in Game #6, Bobby Clarke brutally and expediently slashed Valerie Kharlamov, breaking his ankle and removing a leading Soviet scorer from the tournament. The events taking place were clearly not a game. Phil Esposito would later remark "It was war and, yes, hell for us whether we wanted it or not."

http://archives.cbc.ca/IDD-1-41-318/sports/summit_series

"Many Canadians vividly remember the 1972 Summit Series, and the moment Paul Henderson scored the winning goal in the last electrifying minute of the final game, giving Canada one of its greatest hockey victories ever". The homestand of the series was spread across the country, with games played in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver. Still, that does not begin to provide access for the entire population, so most Canadians experienced the games either on television or radio. That "last electrifiying minute" was a media event as much as it was a hockey moment, and the impact of the series has been due, first to the huge numbers of people who experienced it and, second because the series lives on in video clips, documentary films, and websites. It continues to be a media event.

http://www.cbc.ca/arts/tv/bodychecking.html

There is now a generation of Canadians who do not remember and did not participate in that collective elation. Campfire Stories has discussed how stories inform future generations. In order for a culture to survive, its myths and legends must be reiterated for every generation. It is the responsibility of those who were present in 1972 to pass on the information in the form of a story. So in 2006, the CBC produced the miniseries drama Canada Russia '72, describing it as an "an enduring national myth about determination, pride and heart." Endurance of this sort depends on retelling, and what is being retold is not the story of hockey, but the story of the political and social importance of the series. Hockey continues to be metaphor.

.

.

Another way to measure the importance or the impact of an event, is to look at the way it subsequently changed our lives, or in this case, how it changed hockey. Writing in the Vancouver Sun on Sept 29, 1972, Jim Taylor acknowledged what most of us had seen. Or from the viewpoint of Soviet goaltender Vladislav Tretiak:

http://www.1972summitseries.com

Like any team sport, hockey depends on interractions among the players, certainly. But not just the players on one team. The nature of the game is just as dependent on interractions between opposing teams. Most observers were aware of the profound differences in game style between the NHL and the European leagues. The Soviet and Canadian teams represented the extremes of those style differences. But it is not possible to share the ice for eight games with such a worthy opponent without appreciating, understanding, and absorbing some of his game. Canadian hockey responded to the finest qualities of Soviet play. Yes, Canada had won the series, but the Canadian game would be changed forever.

http://legendsofhockey.net http://www.hhoflegendsclassic.com http://www.bchl.bc.ca

Before 1972 there had been fast, fit, European players of very high calibre, there had been a markedly different style of play based on precision teamwork, and there had been individual personal styles based on speed and agility rather than force and intimidation. But it took the Summit Series to capture our imaginations and make Canadians aware just how exciting and how successful that sort of game could be.

http://www.geocities.com/canadavsrussia http://www.1972summitseries.com http://www.abdcards.com

In September of 1972 a lethargic Canadian squad just returning from golf courses, cottage country, or the banquet and barbecue circuit were mightily surprised by a fast, fit Soviet team that outskated them at every turn. A visibly ragged Canadian team struggled to stay in the play. They were certainly determined, but no one suggested they were playing elegant hockey. The games were scrappy, sometimes brutal, and several incidents were nothing more than sanctioned violence. Prior to 1972, professional hockey players had assumed that the first few games of the season were a sort of tune-up to get everyone in shape. Only the rookies, or the players who were in danger of being cut from the team would worry about their conditioning. That is no longer the case. Players are now expected to more athletic, stronger, quicker, more flexible, better conditioned than in past decades. And they are expected to be that way from the beginning of training camp. With an improvement in the conditioning of players, there is a corresponding increase in the speed at which the game is played. It is a much faster, potentially more exciting game to play. And it is good news for fans who are paying top prices to see top players; they ought to be able to see those players at their best even during the first games of the season.

http://www.legendsofhockey.net http://www.hockeyarchives.info http://www.torino2006.org

The Soviets proved that they were capable of play at the top levels of hockey, although it would be another 17 years before politics would allow Sergei Makarov and Igor Larionov to move to the NHL. Just as importantly, the implication was that, by extension, all European players might be equally capable. So in the years since 1972, the makeup of professional hockey in Canada has been significantly changed. More European Players are now in playing in Canada than ever before, and Ken Dryden has made the point that, once it became clear that the game was no longer solely owned by Canada, there began also to be many more Americans. In 1998, the NHL changed the format of its All-Star game to compete a North American team against a European team.

http://goaliesarchive.com http://www.legendsofhockey.net http://www.bchl.bc.ca

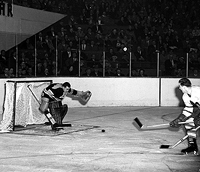

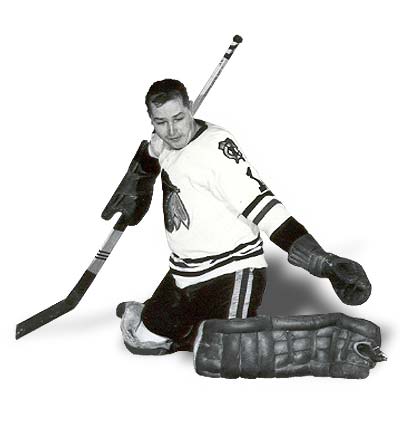

A faster, fitter game with a new prevalence of European players has lent a different sensibility to several aspects of the game, and individual playing styles have been altered to keep pace. Previous generations of Canadian goaltenders for instance, used to try to stay on their feet as much as possible, kicking the puck away. They are now more likely to drop to their knees, taking away the option of a shot along the ice an forcing shooters to use the top half of the net. Certainly the Soviet experience was not the only influence; Glenn Hall had employed a similar style fifteen years earlier, and there continue to be two styles for goaltenders. But it was the series against the Soviet team that got our attention.

http://www.legendsofhockey.net http://www.kendanby.ca

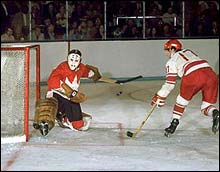

Young and inexperienced, Vladislav Tretiak was supposed to be the weak link in the Soviet team. Instead, he confounded the Canadian goalscorers with his active and agressive style. Playing low to the ice, he was very effective against most low shots Moving to challenge an attacker, he proved to be much more agile and much more difficult an opponent than expected. Tretiak was not a large man, and his method was unorthodox, but he did prove the value of fitness, agility and mobility. How much the Soviet game captured our admiration is evident in Ken Danby's photorealist painting At the Crease. With any number of Canadian models to draw from, Danby's famous goaltender appears to play a Soviet game.

http://www.legendsofhockey.net http://en.wikipedia.org http://www.hockeystars.ru http://bchl.bc.ca

A not insignificant legacy of the Summit Series has been a triumph of common sense over hard headed (some might say thick-headed) machismo. Hockey has always been agressive, and a new faster pace makes that aggression all the more dangerous. Players have to be better protected, and we finally came to accept it. The Soviets were initially derided by Canadian fans because they were all wearing helmets. After all, they played a much less physical game than we, so why would they need helmets. The next generation of players slowly began to It took 25 years, but in 1997, Craig MacTavish retired from hockey as the last man playing without a helmet. And in 2006 the NHL mandated that even referees would begin wearing helmets as well.

Yes we found out a lot of things. We learned from the series and from the Soviets because it was good hockey played by good hockey players. But that alone is not enough. We adopted all these things because the story of the series captured our attention. We became inspired as the story was told and retold, was broadcast and rebroadcast, all the time growing in importance and influence. We mythologize the event, revere the players, and emulate the play. Exactly what legends are supposed to do.

le poêle the stanley cup is made of silver

le poêle the stanley cup is made of silver

the stanley cup is made of silver

Ken Dryden was Canada's goaltender in the Summit Series. His 1983 book The Game is an insightful description of hockey from the inside. Adding a chapter in 2004, he reflects on the changes that have taken place; changes that are largely motivated by the marketplace. The game now is a very big business indeed. There is much more available hockey than in previous years; the NHL alone has gone from 6 teams in 1966 to its present roster of 30 teams. There is much more available money; NHL teams recently agreed to a salary cap of $42.5 million . Even divided among 22 players, the sum makes the Rocket's paycheck look pretty meagre.

The Summit Series was evidence of a large and diverse international audience, and it is not surprising that the owners of the game would respond to take advantage of this gift market. Hockey it is now an international diversified business. Big marketing and big advertising keep the product in front of the public, and big management ensures ticket prices are at exactly the right price point to keep the arena full for nearly every game.

The Vancouver Canucks for instance, are controlled by Orca Bay Sports and Entertainment, the name itself registering the range of enterprises and merchandising that the team encompasses. Orca Bay in turn is owned by the Aquilini Investment Group, Inc. In other cities, ownership has varied from the Walt Disney Corporation (The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim) to the Ontario Teachers Federation Pension Fund (the Toronto Maple Leafs). Hockey at the professional level is not so much a game as it is a diversified portfolio.

Corporate sponsorship for any hockey team is vital. Teams are always alert to the possibility for a promotion, legitimate or otherwise, and they create elaborate campaigns and off-ice promotional events. Pre-game and intermission are times for both sublime and bizarre contests, and of course there is a significant market in the home team swag. Prior to 1972, one of the features that distinguished NHL rinks was the lack of advertising on the rink boards. Now, however, any surface is a potential corporate logo, and brand names are prominently displayed throughout the game. And the players themselves, most visibly in the minor leagues, have become a skating advertisement, multi-logoed jerseys testifying to the involvement of corporate dollars

http://www.hhoflegendsclassic.com http://www.geocities.com/canadavsrussia/1972

Ironically it was in the 1972 series against the Soviets that we most noticed advertising on the rink boards. The most fervent socialists recognised the value of the adverstising dollar. Even more astounding was that the advertisers in Moscow were Canadian and American Companies: CCM; Ford; MacDonald's. The Soviets may not have accepted corporate financial structure, but they certainly understood corporate sponsorship.

http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com

And of course any organization with a labour disruption that lasts an entire year must be considered a major business. The 2004 season was completely cancelled as the players and owners failed to reach a salary agreement. Without NHL hockey, fans had two responses. One response was to go to minor league games and experience the grass roots power and appeal of hockey close up, in a way that is not really possible in the tightly packaged, strictly mediated NHL. The other was to gather around the hotstove in one way or another to talk about hockey, sharing stories, listening to commentary or watching reruns of classic games played in years past. We took the opportunity of a season without NHL hockey to reconnect with the history of the game, to rediscover its core value. Throughout the hiatus, with or without corporate interference, the fans stayed loyal and continue to support the game in ever increasing numbers. This is particularily true of hockey on television, where the price of a ticket is not an obstacle.

le poêle the digital campfire

le poêle the digital campfire

Peter Mansbridge, writing in Macleans Magazine, captures three vital elements in the story of hockey: how well it can conncct us: how early we begin to understand the story: and how often it is reiterated. Fans with season tickets might attend two or three games in a week. Fans that watch television can find sometimes two or three games a day during playoffs. Every game is a variation on the same story and every season is a confirmation that the legend we learned in our childhood is still intact. My family got our first television (a Hallicrafters) when I was five years old. No doubt I would have started watching earlier if that had been possible. It is hard for me to remember a time before hockey; anyone younger than I will likely have been watching the game their entire lives. As children, we knew the names and stats of most of the players in the six team league. By the time I was seven, I was committed to the Canadiens. And regardless whether I lived in Winnipeg, Calgary or Vancouver, I have never had the same unencumbered loyalty for either the Jets, the Flames or the Canucks as I can muster still for the Canadiens. It is more than just nostalgia. What grows up with you stays with you, becomes comforting, necessary. And the sense of being connected to a national hockey culture has become something I can depend on.

Hockey cannot survive in isolation. The game insists on being a team sport and it insists on being a spectator sport. It is best when we can get to the rink to see the game live. In just about any sport, a real game with a real crowd is always much more exciting than having to watch on television. However, the roar of the audience and the intensity of the game transcends the screen and involves the viewer in an immediate experience. We are audibly and visually aware of all the spectators present at the game. Even when we watch it alone or in small groups, we are aware of and connected to every other hockey fan watching the same story unfold.

The oldest and possibly the most successful broadcast sports program in the world is Hockey Night in Canada. The legendary Foster Hewitt began his broadcasts with "Hello Canada and hockey fans in the United States", implying that all of Canada was watching, even if the U.S. was not. Foster was exaggerating, but only slightly. Hockey Night in Canada's theme song has been called our Second National Anthem. Beginning first on Radio in 1931 and then in 1952 on television, every Saturday night during the hockey season, the program has given all of Canada a chance to participate in the same activity. I became a Montéal Canadiens fan even though most of my friends were enamoured of the Toronto Maple Leafs. Their argument was that Toronto was closer, notwithstanding that either team was at least 2000 kilometres away. Watching television, we had no way of knowing that.

By 1972 and the Summit Series, hockey had had 20 years to develop a reasonably large and definitely loyal television audience, but nothing compared to the numbers of people who would be attracted to a top level international series. Hockey Night in Canada had already demonstrated the ability of the medium to unite a Canadian audience. The summit series also proved that the audience was in fact international, and it proved the power of a collective story presented through a mass medium. The television audience for the final game of the series was the largest Canadian audience ever; as many as half the population may mave been in front of a television or a radio. On the other side of the world, it is estimated that 130 million Soviets either watched or listened to the game. The Summit Series radically and permanently changed the expectations of audience. Viewers realized they were watching hockey of a calibre far better than what was then played either in the NHL or the Soviet domestic leagues. Just as a team depends on interraction among its members, two committed opponents can respond to each others' energies and force the game to a better level of play. The faster more skillful game appealed to a wider range of viewers than ever before, and the intensity of the game translated itself into very many different languages. As a story, the summit series transcended most cultural boundaries and created a shared experience mutually understood by otherwise antagonistic audience members.

Marshal McLuhan says, in Understanding Media, that it is the broadcast (the medium) itself that creates the sense of oneness, regardless of the game (the message) being played. That may be true only so far as the medium is connective. Audience is very much a part of the game, and television enlarges the audience far beyond anything that is possible in any single arena. A single broadcast originating from one place can fan out over the entire globe. The potential audience is the entire earth's population. The audience relates to the game being played, and is directly aware of that relationship. But audience members must also be aware of one another. We take both these for granted when the entire audience is in the same building. In a broadcast, the relationships are sometimes not as obvious, but is just as important for the success of the broadcast. We must be made to identify with the players, we must see and hear the crowd, and we must be made conscious of all the millions of people watching and listening to the same event. The media that McLuhan describes is a one way technology. The audience is the recipient, rarely the producer of information. In the early years of digital technology, computers were not easily connected to one another, and media activities engaged people individually. The danger here is increased isolation when individuals find it preferrable to relate to a computer or a television screen. As we get more and more dependent on digital technology it is more and more important to emphasize those activities that people can do together. It is our shared stories and our collective storytelling that will fulfil the creative need. For that reason, it is important to exploit all the ways that connective technologies can carry our stories in several directions, to allow many different contributors to participate in the production, not just the reception, of information. McLuhan calls this a "creative process of knowing". Satellite Hotstove is an intermission feature of Hockey Night in Canada. The name looks back at a simpler time, while using the newest technologies to gather coaches, commentators or players from around the country. Instead of one story originating from one location, now the technology allows several stories from several sources to intersect, to reinforce or contradict one another. And just as in simpler times, the stories shared through this electronic meeting often degenerate into an insoluble argument or impossible comparison. The greater importance of this feature, though, is that it offers proof of hockey fans in other parts of the country or of the world who are plugged into this game in the same way at the same moment.

http://www.cbc.ca/sports/hockey/hnic/hotstove.html

Hockey Day in Canada represents an extension of the television medium. The technology normally used to broadcast a single game across the entire county is instead used to track numerous games and hockey events in various locations across Canada. Rather than seeing one professional game at a time, the audience is shown professional, amateur and minor league games interspersed throughout the entire day. There is a sense of this being a national event, and local involvement and fan participation in hockey games is increased because of the involvement of the media. Because there are games occuring all day long, teams can choose to play during one time of the day, in the hope that they will make it onto national television. Then they can choose to go home and watch what is happening in other places. Stories important to rank and file hockey players and hockey parents at all levels are shared with the rest of the country.

http://www.cbc.ca/sports/hockey/hdic2006

the digital campfire the stanley cup is made of silver

Backcheck; A Hockey Retrospective, National Archives of Canada

http://www.collectionscanada.ca/hockey/024002-3509-e.html

http://www.olympic.org/uk/sports/programme/index_uk.asp?SportCode=IH

http://proicehockey.about.com/od/hockeybooks/tp/business_books.htm

http://www.allbusiness.com/periodicals/topic/2239284-1-2.html

http://www.forbes.com/2004/11/10/04nhland.html

http://washingtontimes.com/upi-breaking/20040820-023512-1510r.htm

Governnment of Canada: Public Policy Forum on the NHL in Canada

http://www.ic.gc.ca/cmb/welcomeic.nsf/ICPages/SpecialReports

Roy MacGregor: The HomeTeam - Fathers and Sons & Hockey, Penguin 1995

http://www.penguin.ca/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,0_9780143013174,00.html

Paul PJ Kennedy: Words on Ice: A Collection of Hockey Prose, Key Porter Books, 2003.

http://www.canadianliving.com

Peter Gzowski, The Game of Our Lives, Heritage House Press, 2004

http://www.heritagehouse.ca/press_releases/gamelives_press.htm

Bruce Dowbigin: Of Ice and Men, McLelland and Stewart, 1999

http://www.mcclelland.com/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9781551990422

Cam Cole, ed.: Ice Level, Canwest Books, 2005

http://www.canada.com/cwb/icelevel.html

David Cruise, Alison Griffiths, Jerry Ciccoritti, , Net Worth, Bernard Zukerman, 1995

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113956

Michael Benedict and D'Arcy Jenish; eds: Canada on Ice : Fifty Years of Great Hockey, Viking, 1998.

http://www.biblio.com/books/3561582.html

Steven Galloway Finnie Walsh, Raincoast Books, 2000

http://services.raincoast.com/scripts/b2b.wsc/fmp/155192/1551928353.htm

Doug Beardsley: Our Game, Raincoast Books 2005

http://services.raincoast.com/scripts/b2b.wsc/browse_subject.htm?hh_subj=261