http://www.pbs.org/circleofstories/stories.html

We are drawn closer to the campfire by the style of presentation. As the story moves online many of the skills needed to understand them are oral and spatial rather than textual. By involving several senses, the author is necessarily increasing the potential for our engagement with the material.

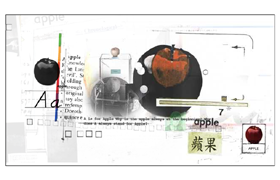

http://www.aisforapple.net/main.htm

An ambitious and inventive use of the campfire has been created by David Clark, a media artist and filmmaker in Halifax, N.S. He describes himself as "an itinerant appropriator, ... fascinated with the associative links that knit fields of knowledge together". Clark's website A is for Apple is a complex network of linked animated lexias. Text is used as part of an image, but the primary means of delivery is audio-visual. The presentation style is much more seductive than simple text-based information. On a simple level, more of the reader's senses are activated by the site and therefore a greater level of excitement ought to be possible. The obvious aural and visual potential more closely resembles the interactivity between the oral storyteller and hir audience than it does the relationship between a print author and the reader. The storyteller has always managed to entertain as well as inform. Hopefully, we will want to pursue the ideas in this website simply because we are enjoying the journey.

But it goes beyond just sensory enjoyment. The interactivity of the A is for Apple is much more immediate, more demanding, and more necessary to the learning experience. Any reading is an active task, an interactive relationship between the reader and the text, but here the reader must engage the material at a number of layers. Choices are necessary at each layer, and the reader assumes a degree of ownership of the learning experience which is extremely stimulating.

A is for Apple presents an interesting juxtaposition, collision if you like, of linear and non-linear presentation modes, and it underscores the changing relationship between the author and the reader. Much as authors (academic authors in particular) would like to think that they are in control of the information they are presenting, and that they control how the information is received, theories of intertextuality would argue such control is not possible. Each reader arrives at the text in a different manner, having come from a different starting point. Most readers understand that we will each have a different relationship with the material, though only a few will recognize the nature of their relationship with the author.

Clark's menu is quite random, so there is no way to even determine whether there is a preferred order to this material. But once an audio clip is opened, the only way to experience it is to listen all the way to the end. There is no practical way to browse or skim the material. The author has relinquished control over the order of lexias, but has maintained control of the presentation within each lexia. The reader is continually and alternately either assuming or relinquishing the responsibility for navigating through the material. The collaboration between author and reader is no longer a peripheral issue. It becomes a necessary and integral part of the process. The fuel for the campfire might be provided by the author, but the reader is the one who does the stoking, thus regulating the size of the blaze.

The process is both active and decisive, creating a sense of ownership that is key to the reader's interest in this site. By taking ownership, the reader is more empowered, more engaged. At the same time, though, the reader cannot be left completely on hir own. Many interactive presentations or hypertexts fail because the lexia are too short, the interactions too frequent and the structure too random to appeal to a reader accustomed to a more lesiurely pace or a more orderly method of delivery. By handing the ownership back and forth, the author continues to influence the structure of the experience while at the same time accepting the contribution of the reader. The collaborative nature of the author/reader relationship also tacitly recognizes and values a level of responsibility on the part of the reader. Just as ownership, responsibility and recognition are important factors in job satisfaction, so too they can be important factors in reader satisfaction.

A is for Apple highlights another aspect of the author/reader relationship, and that is the issue of trust. The earlier examples by David Brown and Alan Beck were published in peer reviewed journals. My own presentations, though not peer reviewed in the same way, have at least been offered at academic conferences, and have undergone some degree of scutiny and discussion among colleagues. Stroicheff's research is supported and maintained on the website of his University. In all these cases there is some measure of respectability afforded by the academic process. In contrast, A is for Appl e is self-published, unjuried, unauthenticated. It is simply there. It offers none of the usual assurances that the information will be of any value. If I am going to spend time reading this information, I would like to know that I am not wasting that time. And if I am to use it as a source for my own research, I have to be certain that the information is correct. Or more accurately, I have to be able to convince myself that the information is not too incorrect.