Diminution

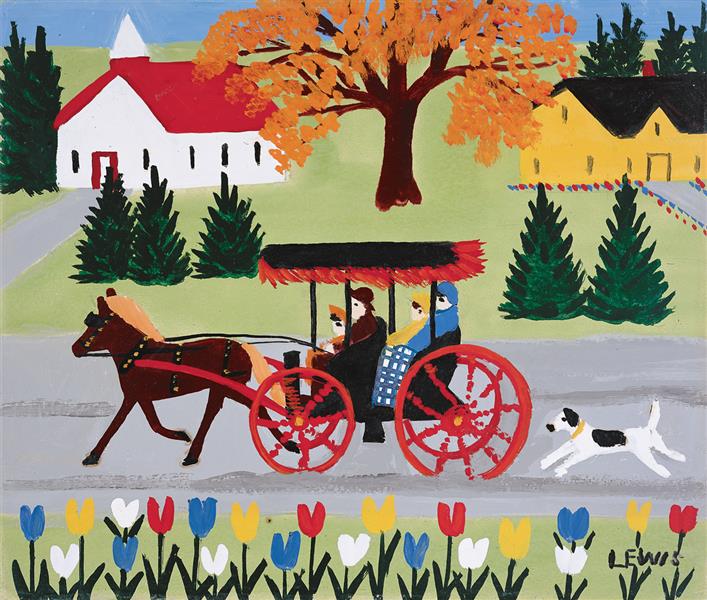

Maud Lewis: Carriage and Dog ca.1965 Private Collection,

https://www.artgalleryofnovascotia.ca/exhibitions/maud-lewis-gallery

We intuitively understand how the perceived size of a figure diminishes as it recedes into the distance. So depth can be rendered almost solely by relative sizes of objects. Maud Lewis' tulips, the carriage, and the buildings only make sense if we interpret them in that way. But this is not confined to Naive Artists. Alex Coleville meticulously plots the geometry and composition of his work. But in Seven Crows, it is only the relative sizes of the birds that gives us any clue as to their location in space.

Alex Coleville: Seven Crows, 1980, Owens Art Gallery Mount Allison University, Sackville NB

http://alexcolville.ca/gallery/alex_colville_1980_seven_crows/

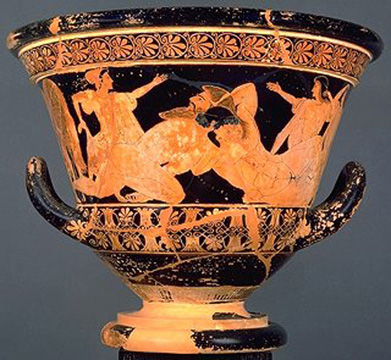

The Greek ceramic painter Euphronios renders the

background figures smaller than those in the foreground. This is consistent with our natural observation,

but

there does not seem to be a geometric rationale to it. Nor is it consistent among all painters.

Even in Euphronios' case, he uses the technique more to emphasize the action between the main characters

than to create a convincing perspective.

Euphronios:Hercules & Antaeus (Greek) Red Figure Crater, ca. 515 BCE,

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Euphronios

A slightly younger krater renders Helios' chariot pulled by four winged horses. Their heads and their hooves progressively diminish in scale satisfactorily. But the overall body length of each horse does not. Nor do the chariot wheels diminish. So the painter here again shows an intuitive understanding of diminution, without being able to apply it consistently.

Helios Rising from the Sea (Greek) Red Figure Krater, ca. 430 BCE,

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1867-0508-1133