Vitruvian Visual Rays

There is an ongoing debate as to whether Romans, and possibly the Greeks, used Linear Perspective as we know it today. Certainly they understood some of the elements. They knew that objects could be foreshortened and appear to recede into the distance. They perceived that straight lines do not always appear horizontal or vertical, and that the angle or slope of a perceived straight line changes according according to its orientation to the viewer. In his introduction to Book VII of De Architectura, Vitruvius says:

....Perspective is the method of sketching a front with the sides withdrawing into the background, the lines all meeting in the centre of a circle ... Agatharcus, in Athens, when Aeschylus was bringing out a tragedy, painted a scene, and left a commentary about it. This led Democritus and Anaxagoras to write on the same subject, showing how, given a centre in a definite place, the lines should naturally correspond with due regard to the point of sight and the divergence of the visual rays, so that by this deception a faithful representation of the appearance of buildings might be given in painted scenery, and so that, though all is drawn on a vertical flat facade, some parts may seem to be withdrawing into the background, and others to be standing out in front.

There was not agreement among Romans about the nature of vision. Lucretius postulated that all things are made of atoms, and that an atom-thin layer or 'image' streams from the surface of an object to enter the eyes. Visual Rays on the other hand, were thought to be produced by the observer and to emanate in a cone shape from the eye. Vitruvius does not spend any time arguing which process is correct. The Visual Ray theory is useful to him in creating the illusion of space. Indeed it is still often used as a model to explain the geometry of One Point Perspective. And though Vitruvius' description of Greek theatre is intriguing in the extreme, Agatharchus' use of perspective will have to remain a mystery. None of his work has survived.

What Vitruvius does not describe is a method for accurately measuring depth in the rendering. So in looking at the colonnade near the top of this wall painting, the columns behave somewhat as expected, getting progressively shorter as they recede, but the spacing between seems quite random. In a true linear projection, those spaces would also be progressive.

What Vitruvius also failed to mention was that a single 'point of sight' should apply throughout the rendering. Painters seem to have applied Vitruvius' method separately to individual objects. So some elements of the composition are convincing, while others are not. Note for instance that, in this fresco, we are meant to be looking up at one of the balconies, while looking down on another. In the second fresco, the colonnades in the rear converge on one point, while the podium in the foreground converges on another.

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscorealeca. ca.50-40 B.C.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscorealeca. ca.50-40 B.C.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017

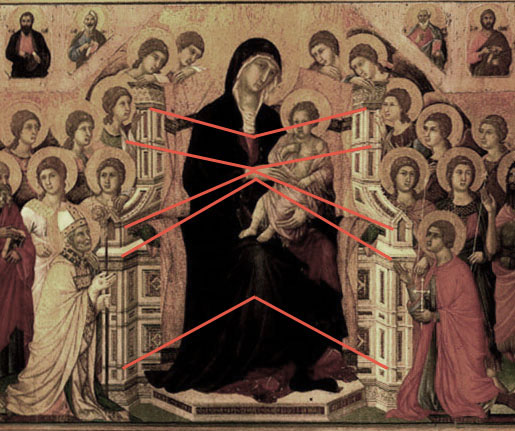

In his Madonna in Glory, Duccio di Buoninsegna rationalized the various lines so that they meet at several points somewhere on a vertical axis. From our current standpoint, with what we now know about Linear Perspective, this looks like an artist groping his way towards an elusive understanding of One Point Perspective. Erwin Panofski makes exactly this case in Perspective as Symbolic Form. But maybe it is not a direct progression towards a true Linear Prespective. It is true that the vertical axis gives the composition a focus and a solidity. Maybe that is all Duccio intended.

The vertical vanishing axis was certainly not universally applied. In Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Allegory of Good Government, there is no recognizable system to the perspective. It is not because Lorenzetti was unaware. In his Anunciation, he clearly demonstrates that he knew how to use a vanishing point. He seems to have made a conscious choice to ignore it. While the confused Perspective in his allegorical city may not be convincing, it does create a kind of functional chaos that is part of an active, thriving city. Lorenzetti apparently felt that if he could achieve that much, a more believable spatial relationship wasn't necessary.

Duccio di Buoninsegna: Madonna in Maesta, Siena Cathedral 1308, reproduced in Beckett; page 42

Ambrogio di Lorenzetti: Allegory of the Good Government, 1338, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/ambrogiolorenzett.htm