Perspective of Status

Fowling scene from the Tomb of Nebamun, ca. 1350 BCE. British Museum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Nebamun

The Tomb of Nebamun contains an image that renders both action and spatial relationships. The figures are of different sizes, but that has nothing to do with their location in space. Rather it serves to establish the status of each character. The nobleman is largest, and his figure dominates the scene. His wife, child and even his boat are rendered smaller than life. It may be argued that this is not really Perspective at all. But this pictorial convention was employed by the Egyptians for over 3000 years. And a similar idea would have another thousand year life in Christian and Buddhist art. So it bears some examination. It is proof that if we believe in the convention, we will accept it as reality.

Blessing Christ between Angels, Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna c. 500 CE

https://www.wga.hu/html_m/zearly/1/4mosaics/2ravenna/4nuovo/index.html

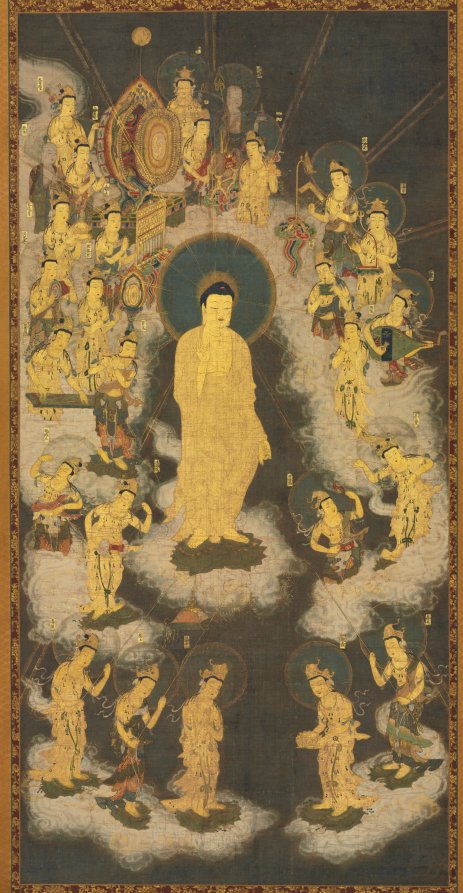

Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Five Planets, 897 CE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhist_art

Ambrogio di Lorenzetti: Allegory of Good Government, 1338, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

http://www.travelingintuscany.com/art/ambrogiolorenzett.htm

In early Christian art, the difference is subtle. In the Sant Apollinaire Nouvo mosaics, the figure of Christ is rendered larger than the angels, but it is within what might be considered natural limits. Examples from this period are rare because between about 725 and 850, most religious art was destroyed by Iconoclasts.

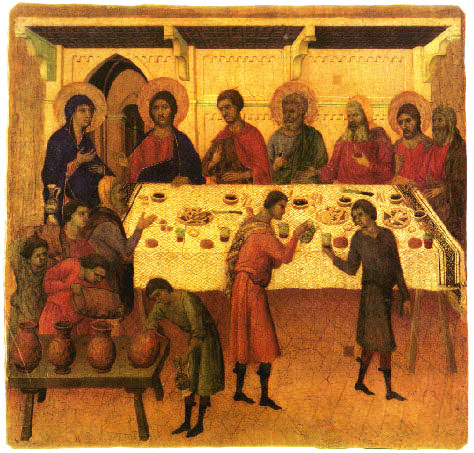

When the Church again accepted Art, status was an even more important consideration. So naturally, in painting, the nobles are depicted larger than the servants, regardless of their location in the composition. In Duccio's Marriage at Cana, servants in the foreground are rendered smaller than Christ and the banqueters behind them. In Ambrogio Lorenzetti's Allegory of Good Government, he renders the Prince and his muses larger than the petitioners in front of him. Believable perspective is not the point here. These are allegorical paintings. What is most important is the clarity of the story and the recognizability of the characters.

Duccio; The Marriage at Cana , Siena, Museo dell' Opera delduomo. 1308

reproduced in Florens Deuchler; Duccio, Milan, Electa Editrice, 1984p131

As a reflection of the power of the Church, the motif of the "Madonna in Glory" emerged, rendering Christ and the Virgin improbably larger than surrounding figures. This system of portrayal requires an unshakeable belief that the universe is governed by a supreme deity, and that all else (including natural observation) submits to that rule.

Giotto: Madonna in Maesta, 1311

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/G/giotto/giotto_madonna_in_glory.jpg.html

Welcoming Descent of Amida (Amida Raigō), Japan, 1300-1333.

The Cleveland Museum of Art

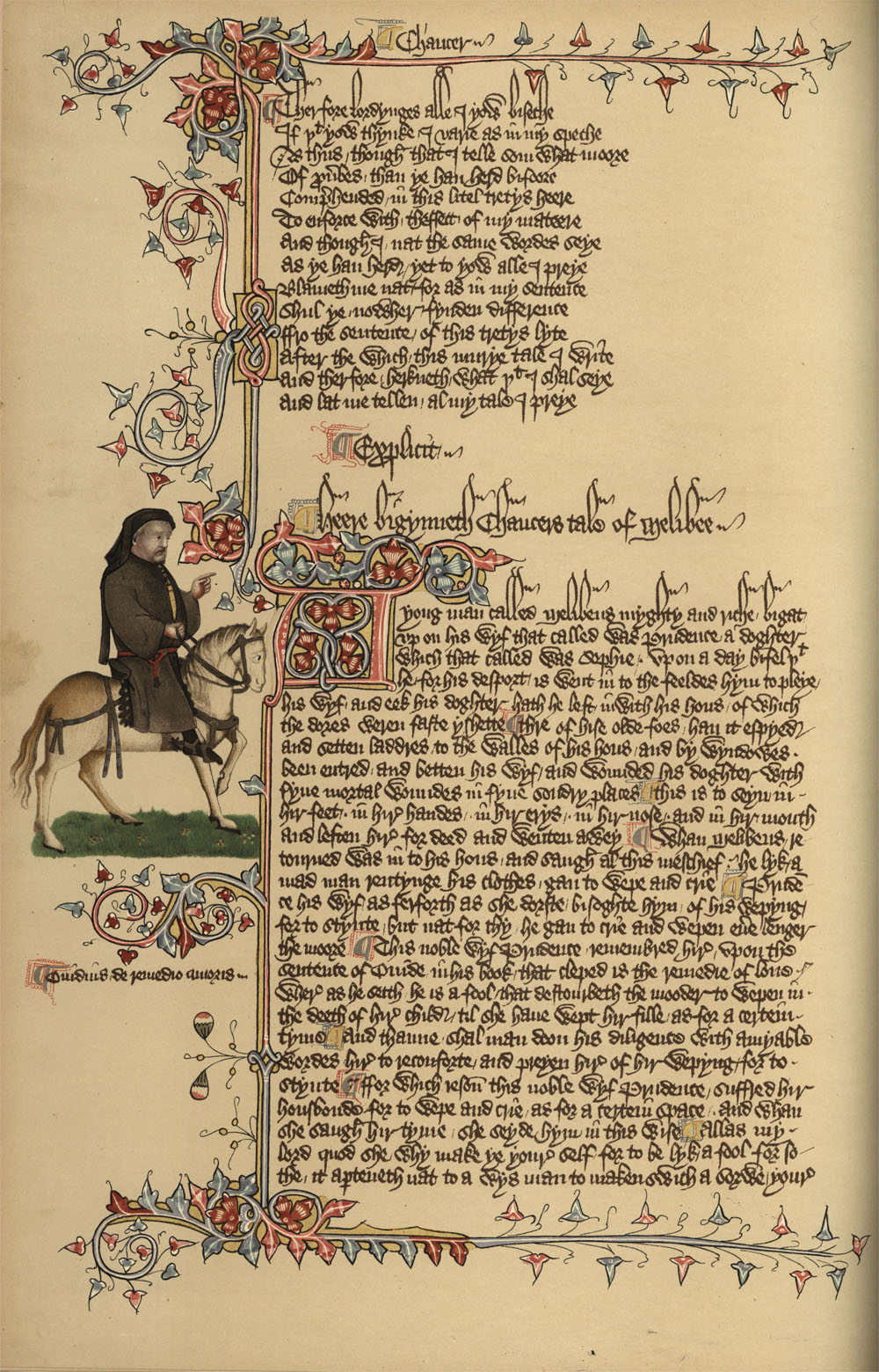

Nor was it confined to religious art. The Ellesmere Manuscript is a copy The Canterbury Tales, illuminated with delightful marginal illustrations. This one is likely a portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer himself, riding an impossibly small horse.

The Canterbury Tales (Ellesmere Manuscript) ca.1400-1410, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll7/id/2828

To the 21st Century eye, this form seems quite implausible, and it is hard for us to imagine how the Medieval mind could accept this form as representing real life. Giotto di Bondone apparently wrestled with this as well, and attempted to make his compositions more natural, always of course within the constrainst of the allegorical convention. In his painting The Lamentation, Giotto attempts some degree of verisimilitude by making his Christ figure only slightly larger than life. We are also fooled because the figure is lying down. If this reclining figure were standing, he would be a 2.5 metre giant.

Giotto: Lamentation, ca 1310

https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/g/giotto/padova/3christ/chris20.html