Sir Tristram

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

This page has moved to https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/tristram/ and is no longer being maintained here. Please visit its new home for updated and corrected texts, images, and links.

13th-century German casket with scenes from story of Tristram and Isolde. By permission of the British Museum. Click the image to see details on the Museum website.

The story of Sir Tristram occupies a huge portion of Malory’s Morte Darthur, and in that story, Tristram’s ill-fated love for La Beale Isoud is central. But Tristram is not only a lover; he is also a most accomplished knight, and Malory makes a point of his skills in fighting, hunting, and harping. Tristram may be Celtic in origin. His Welsh name, Drystan ab Tallwch, appears in Culhwch ac Olwen and in the Welsh triads: in the latter he is one of the Three Enemy-Subduers of the Island of Britain (Triad 19), Three Battle-Diademed Men... (Triad 21), and Three Powerful Swineherds... (Triad 36; this last triad mentions “March” and “Essylt”).

Tristram is closely associated with Cornwall, and may well have been an independent figure gradually absorbed into the Arthurian tradition. To the right is the Tristan Stone, an obelisk that now stands near the road to Fowey in Cornwall. A weathered Latin inscription reads “Drustans hic iacet Cunomori filius” [Drustans son of Cunomorus lies here]. The stone may offer support for the early association of Tristram with Cornwall; the Iron Age hillfort called Castle Dore has been traditionally associated with the story of Tristram and Yseult.

There are many more versions of the Tristram story, medieval and post-medieval, than this page can summarize; what follows is intended to give you a glimpse of the variety of Tristrams, both before and after Malory.

Photo by Jeff Van Campen. Creative Commons license.

Detail from British Library, MS Harley 4389, folio 26r, appears by permission of the British Library.

Despite his apparently Celtic origins, Tristram comes into prominence through Norman, French, and German versions of his story. These include the Anglo-Norman Thomas, whose version (c. 1170) became the basis for Gottfried von Strassburg’s German poem (c. 1210), and for the metrical Middle English Sir Tristrem (late 13th century; this is one of the romances in the Auchinleck manuscript). Malory, however, worked from the French prose Tristan, a work which survives in two versions, dating to the second and third quarters of the 13th century (this is not part of the Vulgate cycle of Arthurian romance, but rather, was written after and influenced by it).

Tristram is also renowned as a hunter: he is the inventor, Malory tells us, of many of the terms of hunting used by gentlemen. There are many medieval and early modern works devoted to hunting. To the right is the title-page of Juliana Berners’ Boke of Hawkynge and Huntynge and Fysshynge, printed by Wynkyn de Worde, c. 1515. Click on the image to read the whole book online (click Show all images in this set once you arrive at the page with this picture) at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

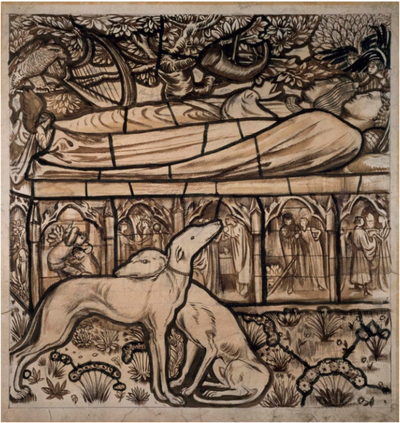

The picture above is the sketch for one of thirteen stained glass panels based on the Tristram story, designed in 1862 for Harden Grange by William Morris & Co. The tomb panel (designed by Edward Burne-Jones), features a pair of dogs. The image comes from the Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource, and appears in accordance with the terms for educational use. Click the image for a larger version and more information from that site.

Tristram’s abilities as a hunter may explain the interest, in many of the versions of his story, in his faithful dog (of course, Arthur has his Cafal, too). This quotation, for example, is taken from Beroul’s late-12th-century romance Tristan :

Anyone who would now like to hear a story that shows the benefits of training an animal should listen to me well. You will hear about Tristan’s good hunting dog. No king or count ever had one like it. He was fast and alert; he was beautiful and he ran well, and his name was Husdent.... [Husdent follows Tristan, who has escaped into the forest in order to be with Isolde; Tristan trains the dog not to bark] Before the month was out, the dog was so well trained that he followed trails without a sound. Whether on snow, on grass, or on ice, he never abandoned his prey, however fleet or agile it might be. Now the dog was a great help to them, and he served them well. If he caught a deer or buck in the woods, he would hide it carefully, covering it with branches. And if he caught it in the open, as he often did, he would throw grass over it. He would then return to his master and lead him to the place where he had killed the deer. Indeed dogs are very useful animals!

The faithful hound also features in a rather surprising way in the Middle English Sir Tristrem (visit the Camelot Project to read the whole thing)n which survives in only one, 14th-century manuscript. In this version of the story, Hodain the dog drinks the fateful love potion along with Tristrem and Ysonde:

An hounde ther was biside

That was ycleped Hodain;

The coupe he licked that tide

Tho doun it sett Bringwain.

Thai loved al in lide

And therof were thai fain.

Togider thai gun abide

In joie and ek in pain

For thought.

In ivel time, to sain,

The drink was ywrought.Tristrem in schip lay

With Ysonde ich night;

Play miri he may

With that worthli wight

In boure night and day.

Al blithe was the knight,

He might with hir play.

That wist Brengwain the bright

As tho.

Thai loved with al her might

And Hodain dede also.

By permission of the British Museum

The tiles above are from Chertsey Abbey, and form part of a series telling the story of Tristram and Iseult. They date from the 13th century. The top tile shows Tristram and Iseult on the boat, while the bottom shows Tristram playing a harp before King Mark. Tristram is a famous harper, too, an attribute picked up on in Edmund Blair Leighton’s 1902 painting Tristan and Isolde, below (image from Wikimedia Commons).

It is with his harp that Tristan, disguised as Tantris, makes his first impression on Isolde in Gottfried von Strassburg’s version of the story:

And so they sent for his harp, and the young Princess, too, was summoned. Lovely Isolde, Love’s true signet, with which in days to come his heart was sealed and locked from all the world save her alone, Isolde also repaired there and attended closely to Tristan as he sat and played his harp. And indeed, now that he had hopes that his misfortunes were over, he was playing better than he had ever played before, for he played to them not as a lifeless man, he went to work with animation, like one in the best of spirits. He regaled them so well with his singing and playing that in that brief space he won the favour of them all, with the result that his fortunes prospered.

Photo © Tate, London, 2012.

La Belle Iseult , by William Morris, 1858. Click the image to read about the painting on the Tate website.

Richard Wagner composed his opera Tristan und Isolde between 1857 and 1859. Click here for a gallery of historic postcards associated with the opera.

Wikimedia Commons image; public domain.

Tristan and Isolde with the Potion, by John William Waterhouse, c. 1916.

Ah, sweet angels, let him dream!

Keep his eyelids! let him seem

Not this fever-wasted wight

Thinn’d and paled before his time,

But the brilliant youthful knight

In the glory of his prime,

Sitting in the gilded barge,

At thy side, thou lovely charge,

Bending gaily o’er thy hand,

Iseult of Ireland!And she too, that princess fair,

If her bloom be now less rare,

Let her have her youth again -

Let her be as she was then!

Let her have her proud dark eyes,

And her petulant quick replies -

Let her sweep her dazzling hand

With its gesture of command,

And shake back her raven hair

With the old imperious air!

As of old, so let her be,

That first Iseult, princess bright,

Chatting with her youthful knight

As he steers her o’er the sea,

Quitting at her father's will

The green isle where she was bred,

And her bower in Ireland,

For the surge-beat Cornish strand;

Where the prince whom she must wed

Dwells on loud Tyntagel’s hill

High above the sounding sea.And that potion rare her mother

Gave her, that her future lord,

Gave her, that King Marc and she,

Might drink it on their marriage-day,

And for ever love each other -

Let her, as she sits on board,

Ah, sweet saints, unwittingly!

See it shine, and take it up,

And to Tristram laughing say:

“Sir Tristram, of thy courtesy,

Pledge me in my golden cup!”

Let them drink it - let their hands

Tremble, and their cheeks be flame,

As they feel the fatal bands

Of a love they dare not name,

With a wild delicious pain,

Twine about their hearts again!

Let the early summer be

Once more round them, and the sea

Blue, and o’er its mirror kind

Let the breath of the May-wind,

Wandering through their drooping sails,

Die on the green fields of Wales!

Let a dream like this restore

What his eye must see no more!