Tolkien and Runes

“Would it be a good thing to provide a runic alphabet? I have had to write one out for several people.”

From the moment The Hobbit appeared in 1937, Tolkien’s readers were fascinated by the runic letters that appeared in the book. The dust jacket, which was Tolkien’s own design, included a border of runes which, when transliterated, read “The Hobbit or There and Back Again, being the record of a year’s journey made by Bilbo Baggins; compiled from his memoirs by J.R.R. Tolkien and published by George Allen & Unwin.” Click here for an image of Tolkien’s artwork and the publisher’s annotation, courtesy of the exhibition (now archived)Treasures from the World'’ Great Libraries, hosted online at the National Library of Australia.

Humphrey Carpenter’s collection, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), includes examples of letters by Tolkien written in runes.

This page offers a brief overview of runic systems, with links to objects and to other resources.

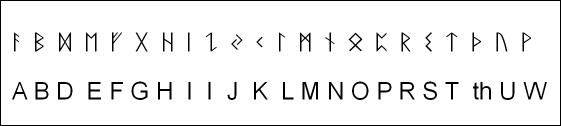

Tolkien’s runes in The Hobbit draw on the Anglo-Saxon system called futhorc, represented to the left; note that the third character represents the combination of th, or thorn. The term futhorc comes from the order in which the first six letters appear in Germanic runic alphabets, called futhark. The first figure below shows the characters of a futhark from a grave at Kylver, Gotland (Sweden), tentatively dated, by its grave goods, to the fifth century.

I have reordered the characters into our alphabetic arrangement. The original order was fu 'th' arkgwhnijpï Rstbemlndo. I haven’t been able to show the second n-form in the illustration above. I have also not been able to show that some of the runes were what is called "retrograde"; that is, that they were reversed. Individual characters could be retrograde, and at first, the order of reading could vary, though the Kylver futhark did read from left to right.

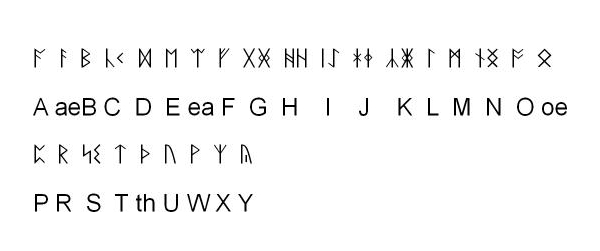

There were 24 characters in the Germanic rune-rows. The Anglo-Saxon futhorc used by Tolkien has 31 distinct characters, some of which have variants. The illustration below makes use of what is called the Dickens-Page system of transliteration to show the Roman equivalents of English epigraphical runes. You should note, however, that I have used upper-case forms for ease of reading, but the convention is to transcribe in lower case:

For an excellent introduction to English runes that is both scholarly and accessible, see R.I. Page, An Introduction to English Runes, 2nd edition (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 1999).

The runes in the illustrations above have been reproduced by means of two runic fonts created by a Norwegian. The fonts are called Gullhornet (for the older runes), and Gullskoen (for the newer forms). They are not representative of any particular futhark or futhorc; rather, they attempt to make as many variants of the various forms available as possible.

Anglo-Saxon runes have names. These are Old English nouns, usually starting with the sound the rune represents (think of our alphabet books: A is for apple, and so on). Thus the rune for f (the first letter of a futhorc, remember), is called feoh, the Old English word for wealth.

We know what these names are thanks to a now largely destroyed manuscript, British Library Cotton Otho B.x. This manuscript included the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem. The poem has 29 stanzas, each beginning with a rune whose meaning is then clarified in the rest of the stanza. The poem is alliterative.

Click here to read the Rune Poem in Old English

Click here to read the Rune Poem in Old English

The manuscript containing this poem was badly damaged by the fire that swept through the Cotton Library in 1731. The Cotton Library was collection of manuscripts started by Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), a famous antiquarian. Much early scholarship on Old English depended on the contents of Cotton’s library, and it is because scholars were in the habit of copying materials from his collection for their own use that we have a copy of the Rune Poem. The Anglo-Saxonist Humfrey Wanley (1672-1726) had copied out the poem, and it was published in George Hickes’s Linguarum veterum Septentrionalium Thesaurus grammatico-criticus et archaeologicus (1703-05). Like many antiquarians, Wanley was fascinated by old letter-forms. In a letter to the Welsh antiquarian Edward Lhwyd, he writes, “I have drawn out many Alphabets, Inscriptions & Specimens of the Saxon & Runic hands, which will be publish’d in Dr Hickes’s book: and have promised to give him a sort of Series of the Saxon Hands from the 7th to the 11th or 12th Centuries” (P.L. Heyworth, ed., The Letters of Humfrey Wanley, p. 199).

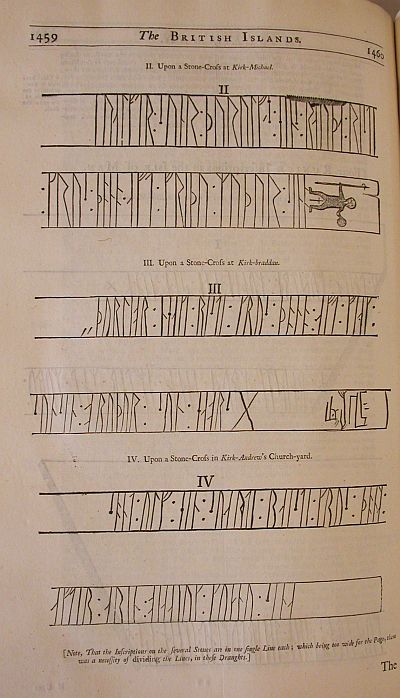

This image is taken from a 1695 edition of William Camden’s Britannia, first published in 1586. It shows illustrations of runic inscriptions from stone crosses. Our library’s department of Rare Books and Special Collections owns quite a few books by the early antiquarians; click here to visit a small page I have put together on some of these.

Visit the Hall of Fame in the Anglo-Saxon Charters site to read more about the early Anglo-Saxonists

Visit the Hall of Fame in the Anglo-Saxon Charters site to read more about the early Anglo-Saxonists

Runes are found on many kinds of objects. The only complete epigraphical futhorc survives on a 10th-century Saxon knife found in the Thames at Battersea. It is called the Seax (knife) of Beagnoth. There are two inscriptions on this large knife; the first is a 28-character futhorc, and the second is the name Beagnoth, either the maker or the owner of the knife. There are some errors in the futhorc.

Click here to see the Seax of Beagnoth on the British Museum’s site

Click here to see the Seax of Beagnoth on the British Museum’s site

There are other objects with runic inscriptions in the British Museum's collection; I have provided links to some below. You can find more by searching for “runes” in the Museum's Collection Search page.

A gold bracteate (stamped gold pendant) from about 450-500, found at Undley in Suffolk, though its runes are Anglo-Frisian

A gold bracteate (stamped gold pendant) from about 450-500, found at Undley in Suffolk, though its runes are Anglo-Frisian

The Franks Casket dates to the first part of the 8th century. It is a whalebone chest carved with Roman, Bibilical and Germanic stories, with inscriptions in Latin and Old English, and in Roman and runic characters

The Franks Casket dates to the first part of the 8th century. It is a whalebone chest carved with Roman, Bibilical and Germanic stories, with inscriptions in Latin and Old English, and in Roman and runic characters

The brooch of Aedwen, an Anglo-Scandinavian item from the first part of the 11th century

The brooch of Aedwen, an Anglo-Scandinavian item from the first part of the 11th century

The objects above are personal items, small and portable. Runes are also found on stones, some of them large stone monuments. Page writes that there are 37 known Anglo-Saxon rune stones, nearly all associated with the Church (p. 130). There are, for example, several famous runic crosses. The image to the left is the Bewcastle Cross, an enormous Northumbrian cross with damaged runic inscriptions. It dates to the first half of the 8th century. It is stylistically similar to the more famous Ruthwell Cross. It is inscribed with both Latin and Old English, and with Roman and runic letters. The runic inscriptions include a version of the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood, also found in the manuscript called The Vercelli Book.

Click here to visit a brief page on the Bewcastle Cross

Click here to visit a brief page on the Bewcastle Cross

Ancient Crosses in Cumbria has images of many crosses, including runic ones

Ancient Crosses in Cumbria has images of many crosses, including runic ones

“More insidious is the way runes are now touched by the flight from reason so characteristic of our pragmatic, scientific and down-to-earth times; the attempt, often in most vulgar terms, to promote some link between runes and the supernatural. There is nothing new about this..., but modern assertions about ‘reading the runes’, linking the script to other fashionable ways of foreseeing the future or of discovering a true self, go beyond a reasoned discussion of the evidence and are likely to lead the study of runes into contempt among the thoughtful.” (R.I. Page, An Introduction to English Runes, 2nd edition, p. xiii)

Tolkien acknowledged that the runes adorning his proposed dust jacket for The Hobbit were “magic in appearance,” but was quick to point out to his publisher their very pragmatic translation. But runes certainly have the appeal that R.I. Page seems to fear. The most popular internet rune site are often linked to the practice of using runes for divination (though you will note that the #3 entry is a debunking site, another high-hit category).

Runes at The Skeptic's Dictionary

Runes at The Skeptic's Dictionary