Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

Reputation

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

While many contemporary historians willingly incorporated into their own work the details from Geoffrey’s Historia, there were critics. One of the most vociferous was William of Newburgh. You will see in the excerpts below from his Historia regum anglicarum (1196-98) that one of his greatest objections to Geoffrey is that Geoffrey uses Latin to tell his story: William thinks that the language carries a kind of authenticity with it, and will therefore help Geoffrey to fool his audience. Notice, too, that William wonders how it could be that other, earlier historians overlooked a figure like Arthur.

While many contemporary historians willingly incorporated into their own work the details from Geoffrey’s Historia, there were critics. One of the most vociferous was William of Newburgh. You will see in the excerpts below from his Historia regum anglicarum (1196-98) that one of his greatest objections to Geoffrey is that Geoffrey uses Latin to tell his story: William thinks that the language carries a kind of authenticity with it, and will therefore help Geoffrey to fool his audience. Notice, too, that William wonders how it could be that other, earlier historians overlooked a figure like Arthur.

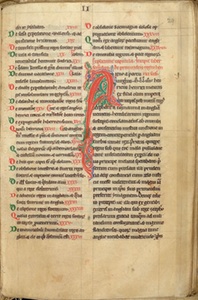

The image to the left is folio 29r of London, BL MS Stowe 62, an early thirteenth-century copy of William’s Historia regum anglicarum. It appears by permission of the British Library: click the thumbnail to see more images from this manuscript on the British Library website.

But in our own days, instead of this practice, a writer has emerged who, in order to expiate the faults of these Britons, weaves the most ridiculous figments of imagination around them, extolling them with the most impudent vanity above the virtues of the Macedonians and the Romans. This man is called Geoffrey, and his other name is Arthur, because he has taken up the fables about Arthur from the old, British figments, has added to them himself, and has cloaked them with the honorable name of history by presenting them with the ornaments of the Latin tongue....

Since these events agree with the historical truth set forth by the Venerable Bede, all the things which that man took care to write about Arthur and either his predecessors after Vortigern or his successors, can be seen to have been partly concoted by himself and partly by others, either because of a frenzied passion for lying or in order to please the Britons, most of whom are known to be so primitive that they are said still to be awaiting the return of Arthur, and will not suffer themselves to hear that he is dead....

For how could the old historians, to whom it was a matter of great concern that nothing worthy of memory should be omitted from what was written,who indeed are known to have committed to memory quite unimportant things, how could they have passed over in silence so incomparable a man, whose deeds were notable above all others? How, I ask, could they have suppressed with silence Arthur and his acts, this king of the Britons who was nobler than Alexander the Great.....

With even greater daring he has published the fallacious prophecies of a certain Merlin, to which he has in any event added many things himself, and has translated them into Latin, [thus offering them] as if they were authentic prophecies, resting on immutable truth....

Another critic was Gerald of Wales, whose account of the discovery of Arthur’s body at Glastonbury is posted on our Arthur in History page. Gerald also tells a story, in his Itinerarium Kambrie (Journey through Wales) I.v, about a Welshman who can spot lies in books. The story is reproduced below as it appears in Lewis Thorpe’s Penguin translation. The picture to the right is the Bishop’s Palace at St. David’s Cathedral in Wales, where Gerald tells us Meilyr was cured.

Another critic was Gerald of Wales, whose account of the discovery of Arthur’s body at Glastonbury is posted on our Arthur in History page. Gerald also tells a story, in his Itinerarium Kambrie (Journey through Wales) I.v, about a Welshman who can spot lies in books. The story is reproduced below as it appears in Lewis Thorpe’s Penguin translation. The picture to the right is the Bishop’s Palace at St. David’s Cathedral in Wales, where Gerald tells us Meilyr was cured.

Visit the St David’s Cathedral website for more pictures, and a history of the buildings.

![]() n our days there lived in the neighbourhood of this City of the Legions a certain Welshman called Meilyr who could explain the occult and foretell the future. He acquired his skill in the following way. One evening... he happened to meet a girl whom he had loved for a long time. She was very beautiful, the spot was an attractive one, and it seemed too good an opportunity to be missed. He was enjoying himself in her arms and tasting her delights, when suddenly, instead of the beautiful girl, he found in his embrace a hairy creature, rough and shaggy, and, indeed, repulsive beyond words. As he stared at the monster his wits deserted him and he became quite mad. He remained in this condition for many years. Eventually he recovered his health in the church of St. David’s, thanks to the virtues of the saintly men of that place. All the same, he retained a very close and most remarkable familiarity with unclean spirits, being able to see them, recognizing them, talking to them and calling them each by his own name, so that with there help he could often prophesy the future... Whenever anyone told a lie in his presence, Meilyr was immediately aware of it, for he saw a demon dancing and exulting on the liar's tongue. Although he was completely illiterate, if he looked at a book which was incorrect, which contained some false statement, or which aimed at deceiving the reader, he immediately put his finger on the offending passage. If you asked him how he knew this, he said that a devil first pointed out the place with its finger.... When he was harrassed beyond endurance by these unclean spirits, Saint John’s Gospel was placed on his lap, and then they all vanished immediately, flying away like so many birds. If the Gospel were afterwards removed and the History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth put there in its place, just to see what would happen, the demons would alight all over his body, and on the book too, staying there longer than usual and being even more demanding.

n our days there lived in the neighbourhood of this City of the Legions a certain Welshman called Meilyr who could explain the occult and foretell the future. He acquired his skill in the following way. One evening... he happened to meet a girl whom he had loved for a long time. She was very beautiful, the spot was an attractive one, and it seemed too good an opportunity to be missed. He was enjoying himself in her arms and tasting her delights, when suddenly, instead of the beautiful girl, he found in his embrace a hairy creature, rough and shaggy, and, indeed, repulsive beyond words. As he stared at the monster his wits deserted him and he became quite mad. He remained in this condition for many years. Eventually he recovered his health in the church of St. David’s, thanks to the virtues of the saintly men of that place. All the same, he retained a very close and most remarkable familiarity with unclean spirits, being able to see them, recognizing them, talking to them and calling them each by his own name, so that with there help he could often prophesy the future... Whenever anyone told a lie in his presence, Meilyr was immediately aware of it, for he saw a demon dancing and exulting on the liar's tongue. Although he was completely illiterate, if he looked at a book which was incorrect, which contained some false statement, or which aimed at deceiving the reader, he immediately put his finger on the offending passage. If you asked him how he knew this, he said that a devil first pointed out the place with its finger.... When he was harrassed beyond endurance by these unclean spirits, Saint John’s Gospel was placed on his lap, and then they all vanished immediately, flying away like so many birds. If the Gospel were afterwards removed and the History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth put there in its place, just to see what would happen, the demons would alight all over his body, and on the book too, staying there longer than usual and being even more demanding.

Despite the protests of William, Gerald, and others, Geoffrey’s Historia was copied and recopied, and the Prophecies had their own very long life as well. Thomas Heywood (1574? - 1641), the dramatist, also wrote a Life of Merlin which was printed twice, in 1641 and 1651. He drew heavily on Geoffrey, as well as on later chroniclers who themselves had drawn on Geoffrey.

In the opening of the Preface, he asserts that Merlin was “a professed Christian, and therefore his Auguries [are] the better to be approved...” Our library subscribes to EEBO, Early English Books Online, a database which contains digital facsimiles of almost every book printed in Britain from 1473 to 1700. You can see the whole of Heywood’s book there. Click here to go to the EEBO homepage and explore (note that if you are connecting from off campus, you will need to configure your computer properly to use subscription-based services; click here to read the Library’s instructions).

Click here to read a modern interpretation of the Prophecies.

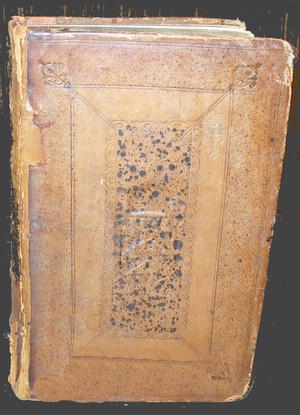

Geoffrey’s Historia was translated into English in 1718 by Aaron Thompson. UBC owns a copy of this edition, and I have created a separate page with several images: click the image of the book cover to the left to go to that page. The files are large, so it may take some time to download.

In Parentheses has translations of many medieval texts. If you click on the Medieval Latin series, you will see, among other things, a later edition of Aaron Thompson’s translation.