King Arthur in History

September 2020: This page has been moved to a new location (https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/king-arthur-in-history/), and is no longer being maintained here. Eventually all my pages from this site will move to their new home at my domain, but it will take quite a while for the migration to be complete. As each page moves, I will add this message to it. The pages should continue to function on their old server, with their old URLs, for the foreseeable future: I will not take them down until all my pages have migrated.

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

This page includes some of the material covered in English 344, in the introductory lectures about the historical King Arthur and the literary development of the legend. For a chronological listing of the references we have discussed in class during the introductory lectures, go to the Arthurian Chronology page.

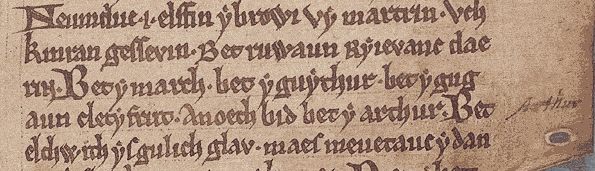

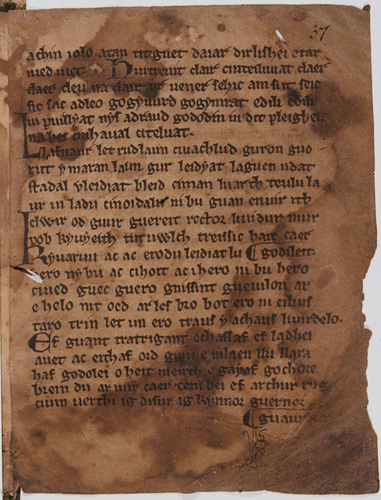

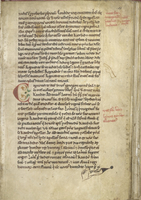

Cardiff Central Library MS 2.81. By permission of Cardiff Libraries and Information Services.

The image above is from the Book of Aneirin, the manuscript that contains the Gododdin. You can view the whole manuscript on the People’s Collection Wales site.

Ef guant tratrigant echassaf

ef ladhei auet ac eithaf

oid guiu e mlaen llu llarahaf

godolei o heit meirch e gayaf

gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur

ig kynnor guernor guaurdur.He pierced over three hundred of the finest

He slew both the centre and the flanks

He was worthy in the front of a most generous army

He gave out gifts of a herd of steeds in the winter

He fed black ravens on the wall

Of the fortress, although he was no Arthur

He gave support in battle

In the forefront, an alder-shield was Gwawrddur.

The manuscript belongs to the 13th century, though the poem is much older. To read more about the language of Aneirin, poet of the Gododdin, visit the BBC’s Story of Welsh homepage. You can also visit the Gododdin page I created for another class.

The map to the right shows Britain at the historical period referred to in the Gododdin.

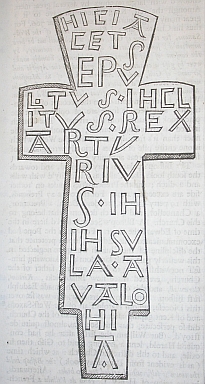

BL MS Harley 3859. By permission of the British Library.

In illo tempore Saxones inualescebant in[At that time the Saxons increased in numbers and grew in Britain. After the death of Hengist, Octa, his son, came down from the north part of Britain to the kingdom of the Kentishmen, and from there are sprung the kings of the Kentishmen. Then Arthur fought at that time against them in those days along with the kings of the Britons, but he was their leader in battles.]

multitudine et crescebant in brittannia.

Mortuo autem Hengisto octha filius eius transi-

uit de sinistrali parte brittanie ad reg

-num cantorum. et de ipso orti sunt reges cantorum.

Tunc arthur pugnabat contra illos.

in illis diebus cum regibus brittonum. sed ipse dux erat

bellorum.

Click here to go to an online reconstruction of the whole of the Latin text.The first battle was at the mouth of the river called Glein. The second, the third, the fourth and the fifth were on another river, called the Douglas, which is in the country of Linnuis. The sixth battle was on the river called Bassas. The seventh battle was in Celyddon Forest, that is, the Battle of Celyddon Coed. The eighth battle was at Guinnion fort, and in it Arthur carried the image of the holy Mary, the everlasting virgin, on his shoulder, and the heathen were put to flight that day, and there was great slaughter upon them, through the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the power of the Holy Virgin Mary, his mother. The ninth battle was fought in the city of the Legion. The tenth battle was fought on the bank of the river called Tryfrwyd. The eleventh battle was on the hill called Agned. The twelfth battle was on Badon hill and in it nine hundred and sixty men fell in one day, from a single charge of Arthur’s, and no one laid them low save he alone, and he was victorious in all his campaigns.

Note that the word for “battle” is Latin in the first instance [Bellum Badonis] and Welsh in the second [Gueith Camlann]

The Battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut fell: and there was plague in Britain and Ireland

8. Bet Gwalchmei ym Peryton

ir diliv y dyneton

in Llan Padarn bet Kinon.

12. Bet mab Ossvran yg Camlan

gvydi llauer kywlavan

bet Bedwir in alld Tryvan.

13. Bet Owein ab Urien im pedryael bid

dan gverid Llan Morvael

in Abererch Riderch Hael.

14. Guydi gurum a choch a chein

a goruytaur maur minrein

in Llan Helet bet Owein.

44. Bet y March, bet y Guythur,

bet y Gugaun Cledyfrut

anoeth bid bet y Arthur

The

grave of Gwalchmei is in Peryddon

as a reproach to men;

at Llanbadarn is the grave of Cynon.

The grave

of Osfran’s son is at Camlan,

after many a slaughter;

the grave of Bedwyr is on Tryfan hill.

The grave

of Owein son of Urien is in a square grave

under the earth of Llanforfael;

at Abererch is Rhydderch the Generous.

After things

blue and red and fair

and great steeds with taut necks

at Llanheledd is the grave of Owein

.

There is a

grave for March, a grave for Gwythur,

a grave for Gwgawn Red-sword;

the world’s wonder/ difficutly (anoeth) a grave for Arthur.

The image above shows the Arthurian reference as it appears in the Black Book of Carmarthen, National Library of Wales MS Peniarth 1 (image appears by permission of the NLW). Click the thumbnail above to view the whole manuscript; the excerpt above is found on fol. 34r. A small window will open: to find the folio and see it in full view, you will need to click the full screen arrow, and call up the Contents sidebar to see thumbnails of all the folios.

Notice that a later annotator has labelled this part of the text in the margin.

From

Pa gwr

Though Arthur

was but playing,

blood was flowing

in the hall of Afarnach

fighting with a hag.

He pierced the cudgel-head

in the halls of Dissethach.

On the mount of Eidyn

they fought with Dog-heads;

by the hundred they fell.

They fell by the hundred

before Bedwyr the Fine-sinewed

on the strand of Tryfrwyd

Fighting with Garwlwyd....

I saw Cei in haste;

prince of plunder,

the tall man was hostile

His revenge was heavy;

his anger was sharp.

When he drank from the buffalo horn

he would drink for four;

when he came into battle

he would strike like a hundred.

Unless it were God who did it,

Cei’s death could not be achieved...

From Preiddeu Annwn

I will praise the Lord, the Sovereign, the King of the land,

who has extended his rule over the strand of the world.

Well equipped was the prison of Gwair in Caer Siddi

according to the story of Pwyll and Pryderi.

None before him went to it,

to the heavy blue chain; it was a faithful servant whom it restrained,

and before the spoils of Annwn sadly he sang.

And until Judgement Day our bardic song will last.

Three shiploads of Prydwen we went to it;

except for seven, none returned from Caer Siddi.

In Caer Pedryfan, four-sided,

my eulogy, from the cauldron it was spoken.

By the breath of nine maidens it was kindled.

The cauldron of the Head of Annwyn, what is its custom,

dark about its edge with pearl?

It does not boil a coward’s food; it has not been so destined.

The sword of Lluch Lleawg was raised to it,

and in the hand of Lleminawg it was left.

And before the door of the gate of hell, lanterns burned.

And when we went with Arthur, renowned conflict,

except for seven, none returned from Caer Feddwid...

Pa gwr is in NLW MS Peniarth 1, the Black Book of Carmarthen, starting on folio 47v. When you click the thumbnail, a small window will open: to find the folio and see it in full view, you will need to click the full screen arrow, and if it is not already displayed, call up the Contents sidebar to see thumbnails of all the folios.

Preiddeu Annwn is in NLW MS Peniarth 2, the Book of Taliesin, starting on folio 25v. When you click the thumbnail, a small window will open: to find the folio and see it in full view, you will need to click the full screen arrow, and if it is not already displayed, call up the Contents sidebar to see thumbnails of all the folios.

his is that Arthur about whom the foolish tales of the Britons rave even today; one who is clearly worthy to be told about in truthful histories rather than to be dreamed about in deceitful fables, since for a long time he sustained his ailing nation, and sharpened the unbroken minds of his people to war. (William of Malmesbury)

ut in our own days, instead of this practice, a writer has emerged who, in order to expiate the faults of these Britons, weaves the most ridiculous figments of imagination around them, extolling them with the most impudent vanity above the virtues of the Macedonians and the Romans. This man is called Geoffrey, and his other name is Arthur, because he has taken up the fables about Arthur from the old, British figments, has added to them himself, and has cloaked them with the honorable name of history by presenting them with the ornaments of the Latin tongue. (William of Newburgh)

Gerald of Wales (d. 1223) writes that he was present at the exhumation of King Arthur from a grave discovered at Glastonbury Abbey around 1190 or 1191; this is part of his account:

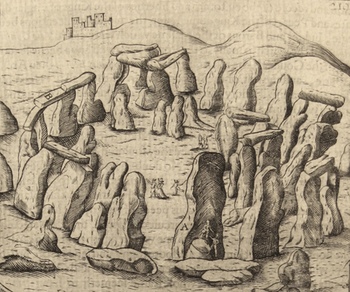

Geoffrey and British History

BL MS Royal 13 D v, folio 1r

BL MS Royal 13 D v, folio 1rMerlin tells Uther the meaning of a comet:

For that star signifies you, as does the fiery dragon beneath the star. The ray which stretches towards the shores of Gaul portends your future son, who will be most powerful, and whose power will extend over all the kingdoms which he will protect. And the other ray signifies your daughter, whose sons and grandsons will hold the kingship of Britain in turn.

Uther tricks Ygerna and Arthur is conceived:

And thus the king spent the night with Ygerna and relieved himself through the sexual relations he desired. He deceived her through the false appearance which he had assumed. He also deceived her with the false words which he carefully composed, for he said that he had come secretly from the besieged camp so that he could see to the thing which was so dear to him, and also to his town. She, believing him, refused him nothing that he asked. Also that night was conceived that most famous of men, Arthur, who afterwards through his wonderful bravery won great renown.

Arthur comes to the throne:

Now Arthur was a youth of fifteen years, of outstanding virtue and generosity. His innate goodness gave him such great grace that he was loved by almost all the people.... Arthur, because his strength was linked with generosity, decided to harass the Saxons so that he could enrich the household which served him with their wealth. Righteousness also moved him, for he ought by hereditary right to have the rule of the whole kingdom.

Arthur is victorious in his war with the Romans:

This outcome was established by divine power, for as in former times the ancestors of those Romans had harrassed the ancestors of the Britons with invidious iniquities, so now those Britons strove to defend the liberty which the others sought to take away from them, refusing to pay the tribute which had been unjustly demanded of them.

Arthur’s death:

But that most famous king Arthur was mortally wounded; Arthur having been taken from there to the island of Avalon for the healing of his wounds, he handed over the crown of Britain to his cousin Constantine, son of Cador Duke of Cornwall, in the year 542 after the incarnation of our Lord. May his soul rest in peace.

BL MS Lansdowne 732, folio 9r

BL MS Lansdowne 732, folio 9r BL MS Egerton 3142, folio 9r

BL MS Egerton 3142, folio 9r

Thumbnails by permission of the British Library. Click the images to go to larger versions on the BL site.