The Arthur of the Welsh

THIS PAGE IS NO LONGER BEING MAINTAINED ON THIS SITE. PLEASE VISIT ITS NEW LOCATION, https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/the-arthur-of-the-welsh/, FOR UPDATED CONTENT, IMAGES, AND LINKS

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

One of the earliest Welsh poems to feature Arthur is Preiddeu Annwn (The Spoils of Annwn). Preiddeu Annwn (sometimes Annwfn) may date to the tenth century, and tells of the voyage by Arthur and his men to Caer Siddi to retrieve a mysterious cauldron. Caer Siddi means Castle of the Faeries—Siddi is like the Irish word Sidhe. The speaker is the legendary harper Taliesin. The poem is incomplete and enigmatic. It suggests that there was a body of legendary Welsh material associated with Arthur well before Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia regum Britannie.

Sarah Higley’s Preiddeu Annwn page includes the Welsh text and sound files, as well as a translation of the poem

Preiddeu Annwn is woven into the narrative of a modern Arthurian fantasy, the Fionavar Tapestry, by the Canadian writer Guy Gavriel Kay. Clicking on the cover image on the left will take you to the authorized Guy Gavriel Kay website. The selection below is part of a conversation between a character called Flidais and the reincarnation of Guinevere, from the third book of the trilogy, The Darkest Road (1986):

His voice went even deeper, and suddenly he chanted, “I have been in many shapes. I have been the blade of a sword, a star, a lantern light, a harp and a harper, both.” He paused, saw something spark in her eyes, ended diffidently, “I have fought, though small, in battle before the Ruler of Britain.”

“I remember!” she said, laughing now. “Wise child, spoiled child. You liked riddles, didn’t you? I remember you, Taliesin.” She stood up. Brendel leaped to the dock and helped her alight.

“I have been in many shapes,” Flidais said again, “but I was his harper once.”

She nodded, very tall on the stone dock, looking down at him, memory playing in her eyes and about her mouth. Then there came a change. Both men saw it and were suddenly still.

“You sailed with him, didn’t you?” said Guinevere. “You sailed in the first Prydwen.”

Flidais’ smile faded. “I did, Lady,” he said. “I went with the Warrior to Caer Sidi, which is Cader Sedat here. I wrote of it, of that voyage. You will remember.” He drew breath and recited:

“Thrice the fullness of Prydwen we went with Arthur,

Except seven, none returned from—”

He stopped abruptly at her gesture.

There are Arthurian stories in the collection of Welsh prose commonly referred to as The Mabinogion (from Victorian translator Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation). There are in fact several different kinds of narratives, of differing dates, grouped under this heading. The Four Branches of the Mabinogi (to use the preferred designation for the core texts) are not Arthurian stories (though they are very concerned with kingship and rule), but motifs familiar to students of Arthurian literature occur here: for example Bendigeidfran, or Bran the Blessed, from the second branch, is often understood to be the prototype of the Fisher King of the Grail legend.

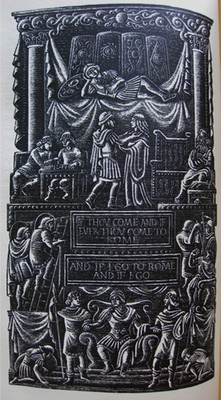

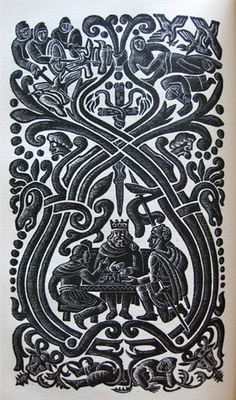

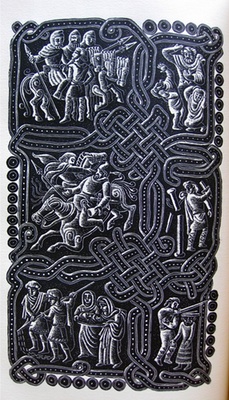

If you pick up a translation of The Mabinogion today, you will find, not only the Four Branches, but also a collection of texts which are specifically about Arthur. Some of these seem to be independent Welsh tales; others are either adaptations of French Arthurian romances, or evidence for a common source for these French and Welsh texts. We are reading several of these for class: Culhwch and Olwen, the Dream of Maxen, and Peredur. We will also refer briefly to the Dream of Rhonabwy. The images above are illustrations for Maxen, Rhonabwy, and Peredur, done by Dorothea Braby for the 1948 Golden Cockerel edition of the Mabinogion. You can read about this edition at Books and Vines. You might also be interested in my page for the Golden Cockerel Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, also with illustrations by Dorothea Braby. I am most grateful to the artist’s estate for permission to share those images.

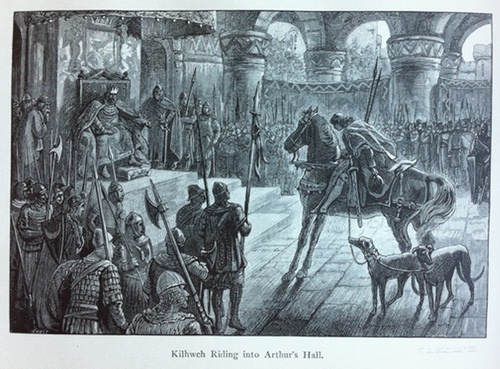

Below is the opening in Welsh of Culhwch ac Olwen, one of the prose narratives we are reading for class. It is found (with the Four Branches ) in the Red Book of Hergest (c. 1400) and the White Book of Rhydderch (c. 1325). Culhwch is probably the earliest Welsh prose text, perhaps taking shape just before the eleventh century. The scene is Culhwch’s arrival at his cousin Arthur’s court, pictured below in an illustration to Sidney Lanier’s 1881 adaptation in The Boy’s Mabinogion.

Mynet a oruc y mab ar orwyd pennlluchlwyt pedwar gayaf gauylgygwng carngragen, a frwyn eur kymibiawc yn y penn. Ac ystrodur eur anllawd y danaw, a deu par aryanhyeit lliueit yn y law. Gleif (ennillec) yn y law, kyuelin dogyn gwr yndi o drum hyt awch. Y gwaet y ar y gwynt a dygyrchei; bydei kynt no’r gwlithin kyntaf o’r konyn hyt y llawr, pan uei uwyaf y gwlith mis Meheuin. Cledyf eurdwrn ar y glun a racllauyn eur itaw, ac ayn eurcrwydyr arnaw, a lliw lluchet nef yndi, a lloring elifeint yndi. A deu uilgi uronwynyon ury chyon racdaw, a gordtorch rudeur am uynwgyl pob un o cnwch yscwyd hyt yskyuarn.... Llenn borfor pedeir ael ymdanaw, ac aual rudeur vrth pob ael iti. Can mu oed werth pob aual. Gwerth trychan mu o eur gwerthuawr a oed yn y archenat a’e warthafleu (sangharwy), o benn y glun hyt ym blayn y uys.

You can read more about the Mabinogion on this page on Welsh Prose that I put together for another class.

eoffrey of Monmouth places Arthur’s famous plenary court at Caerleon-on-Usk, in south Wales, describing the city in ways which may suggest some personal knowledge:

eoffrey of Monmouth places Arthur’s famous plenary court at Caerleon-on-Usk, in south Wales, describing the city in ways which may suggest some personal knowledge:

Situated as it is in Glamorganshire [today, Monmouthshire], on the River Usk, not far from the Severn Sea, in a most pleasant position, and being richer in material wealth than other townships, this city was eminently suitable for such a ceremony. The river which I have named flowed by it on one side, and up this the kings and princes who were to come from across the sea could be carried in a fleet of ships. On the other side, which was flanked by meadows and wooded groves, they had adorned the city with royal palaces, and by the gold-painted gables of its roofs it was a match for Rome.... [IX.12]

Caerleon means “City of the Legions.” The city has an extensive website, which includes a history section with information about the area’s Roman past, and an extensive section on the Arthurian associations.