Merlin

THIS PAGE HAS MOVED TO https://sianechard.ca/web-pages/merlin/ AND IS NO LONGER BEING MAINTAINED HERE. PLEASE VISIT ITS NEW LOCATION FOR UPDATED CONTENT, LINKS, AND IMAGES.

Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

This page contains a few of the texts, Welsh and Latin, that I have referred to in class when talking about Merlin. It is not intended to trace the whole of Merlin’s development, or to list every source; it is simply meant to give you a taste of Merlin’s early history. You may also want to visit our course page on The Arthur of the Welsh.

The picture at the top of the page is the Battersea Cauldron, which is now in the British Museum. Read more about it here.

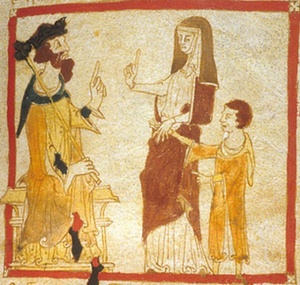

The story of Merlin and the two dragons, which initiates the prophecy section of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britannie, expands on the account, found in Nennius, of the boy Ambrosius, who makes this prophecy to Vortigern. The image on the right, a detail from BL Egerton 3028, folio 24r (which appears by permission of the British Library), shows the boy Merlin and his mother before Vortigern. The manuscript is an illustrated copy of Wace, Roman de Brut (an Anglo-Norman adaptation of the Historia regum Britannie of Geoffrey of Monmouth). Click the thumbnail to go to many more images from this manuscript on the British Library website.

The story of Merlin and the two dragons, which initiates the prophecy section of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britannie, expands on the account, found in Nennius, of the boy Ambrosius, who makes this prophecy to Vortigern. The image on the right, a detail from BL Egerton 3028, folio 24r (which appears by permission of the British Library), shows the boy Merlin and his mother before Vortigern. The manuscript is an illustrated copy of Wace, Roman de Brut (an Anglo-Norman adaptation of the Historia regum Britannie of Geoffrey of Monmouth). Click the thumbnail to go to many more images from this manuscript on the British Library website.

In the account in Nennius, the boy orders Vortigern’s men to dig under the tower. They discover a lake, with two vessels in it. Between the vessels is a cloth, along with a white worm and a red worm. The two worms awake, and fight, and the boy explains the meaning:

The cloth represents your kingdom; the two worms are two dragons; the red worm is your dragon; and the lake stands for this world. But that white dragon is the dragon of those people who seized many peoples and regions in Britain, and they will reach almost from sea to sea, and afterwards our people will arise, and they will manfully throw the English people across the sea. (c. 42)

Merlin makes his prophecy to prevent Vortigern from killing him to use his blood to cement the stones of his tower. The tower, and hence the location of Merlin’s prophecies, is traditionally given as Dinas Emrys, in Snowdonia in northern Wales.

There is a page for Dinas Emrys Castle on the Castle Wales site, and an exploration of references to, and the archaeology of, the site at Early British Kingdoms: Dinas Emrys.

As with Arthur, so with Merlin: it is Geoffrey who fills in many of the details of Merlin’s story, attributing to him such feats as moving Stonehenge from Ireland to England, and giving Uther the appearance of Gorlois so that he can sleep with Ygerna. Geoffrey seems once again, however, to have been working at least in part from Welsh traditions. In his Vita Merlini, Merlin, driven mad after a battle in which his men are killed, laments their loss in this way:

O Christ, God of heaven, what shall I do? What place is there on earth where I can live? I see there is nothing here to eat: no grass on the ground, no acorns on the tree.

Nineteen were the apple trees which once stood here with their fruit: they stand so no longer. Who, who has stolen them from me? Where have they gone so suddenly? Now I see them, now not. So Fate both supports and opposes me, letting me see and preventing me from seeing.

Now the apples fail me, and all else besides. The forest stands leafless, fruitless. It is a double affliction: I can get no cover from the leaves or nourishment from the fruit. Winter and the rainstorms borne on the south wind have taken them, every one. If I happen to find turnips deep in the ground, hungry swine and greedy boars rush up and snatch the turnips from me as I pull them up out of the soil.

[The images from NLW MS Peniarth 1 appear by permission of the National Library of Wales]

There is a Welsh poem preserved in the Black Book of Carmarthen which connects Merlin with apples. The poem is traditionally called Yr Afallennau. It is immediately followed by Yr Oianau, in which the speaker addresses a pig. The third Merlinian poem (and the only one of the three that actually names Merlin) is the Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin, or the Conversation between Merlin and Taliesin. Click the thumbnails above to go to the National Library of Wales site to see pages from the digital version of the Black Book (the NLW has reorganized their digital material, so the thumbnails now open the main manuscript viewer; use the Contents sidebar to navigate to the correct folio). Folio 24v (the left thumbnail) is the opening of Afallenau. Folio 29v, the middle thumbnail, is from Oianau (the poem begins on folio 26v), and the right thumbnail is folio 3v of the Ymddiddan (the poem begins on folio 1r). Taliesin also appears in Geoffrey’s Vita Merlini, and he and Merlin do have a long conversation.

Below is the first stanza in translation of Yr Afallennau ; note that the speaker also addresses a pig:

Sweet apple tree, sweet its branches,

bearing precious fruit, famed as mine.

And I will prophesy before the owner of Machrau:

in Machafwy Vale on a Wednesday of blood,

rejoicing to Lloegr, exceeding red blades.

Oia, little pig! Thursday will come,

rejoicing to the Welsh, exceeding great battles,

swift swords defending Cyminod,

slaughter of Saxons on ashen spears

and playing ball with their heads.

Click here to learn more about medieval Welsh poetry, on a page I created for another class.

You have already seen Merlin’s prophecies in the Historia regum Britannie. This is a common presentation of Merlin in early Welsh literature. In the poem Armes Prydein Fawr [The Great Prophecy of Britain ], the name “Myrdin” appears at the beginning of one stanza. The image is the section of the manuscript which includes the name: the first line begins “Dysgogan myrdin kyferueyd hyn.”

Note that while the manuscript (the Book of Taliesin, now MS Peniarth 2 in the National Library of Wales) is a fourteenth-century copy, the poem is much earlier, usually dated to c. 930 - 937. The section below of Armes Prydein deals with the arrival of the Saxons: you can see the word “saesson” in the eighth line, second word from the left. The Welsh word for “English” today is “Saeson” (the noun) and “Saesneg” (the adjective).

Myrddin tells us how

An assembly at Aber Peryddon

Will bring the High King’s stewards

(They will moan of death)

To gather taxes

The Cymry will not pay.

Mary’s Mabon, sovereign Word,

Unbroken by Saxon battery!

Down with Gwtheyrn’s pariahs!

Foreign foes will go into exile,

No welcome anywhere, no land given -

Rivers will be strange to them everywhere!

Hengist and Horsa bought Thanet

With deceit and guile; since then

They have grown ever stronger.

Merlin chastises the British:

h, the madness of the Britons, whose overflowing riches lead them to seek even more than they ought! They do not wish to enjoy peace, but are goaded by a Fury. They mix civil strife and domestic battles. They allow the churches of the Lord to fall to ruin, and they drive its holy bishops to remote lands. The nephews of the Cornish boar disturb everything. Laying ambushes for each other, they kill each other with their wicked swords, nor are they willing to wait to accede to the kingdom by law, but rather, they seize the crown by force. The fourth one to come after them will be crueller and harsher. A sea-wolf, battling him, will conquer him and, having been conquered, he will flee across the Severn into barbarous lands. The same wolf will encircle Caerceri with siege, and by means of sparrows [or plaice or turbot or flounder...] will drive its houses and walls to the ground.

h, the madness of the Britons, whose overflowing riches lead them to seek even more than they ought! They do not wish to enjoy peace, but are goaded by a Fury. They mix civil strife and domestic battles. They allow the churches of the Lord to fall to ruin, and they drive its holy bishops to remote lands. The nephews of the Cornish boar disturb everything. Laying ambushes for each other, they kill each other with their wicked swords, nor are they willing to wait to accede to the kingdom by law, but rather, they seize the crown by force. The fourth one to come after them will be crueller and harsher. A sea-wolf, battling him, will conquer him and, having been conquered, he will flee across the Severn into barbarous lands. The same wolf will encircle Caerceri with siege, and by means of sparrows [or plaice or turbot or flounder...] will drive its houses and walls to the ground.

Merlin predicts social anarchy after the arrival of the Normans:

hen peace and faith and virtue will all depart, and there will be civil war throughout the lands, and man will betray his fellow, and no friend will be found. The husband, despising his wife, will mate with whores, and the wife will join with whomever she desires, despising her husband. Honour for the churches will not remain, and the order will perish. Then bishops will bear arms, then they will follow the camps, they will place towers and walls on sacred ground and give to soldiers what they ought to give to the poor.

hen peace and faith and virtue will all depart, and there will be civil war throughout the lands, and man will betray his fellow, and no friend will be found. The husband, despising his wife, will mate with whores, and the wife will join with whomever she desires, despising her husband. Honour for the churches will not remain, and the order will perish. Then bishops will bear arms, then they will follow the camps, they will place towers and walls on sacred ground and give to soldiers what they ought to give to the poor.

While many of the prophecies in the Historia and in the Vita are enigmatic, some are clearly associated with contemporary events. Below, for example, is a prophecy from the Vita by Merlin's sister Ganieda: John Jay Parry argued that this passage referred to the battle of Coleshill, Flint, in 1150, when Owein Gwynedd defeated Ranulf, earl of Chester, and Madoc ab Maredudd, king of Powys.

he Armorican boar, protected by an ancient oak, takes away the moon, waving swords behind backs. I see two stars at war with wild beast under the hill of Urien, where the men of Deira and the men of Gwent convened when the great Coel was ruling. O, how the men flow with sweat and the ground with gore, as wounds are given to foreign people! A star, having collided with another, falls into the shadows, hiding her own light when the light is restored.