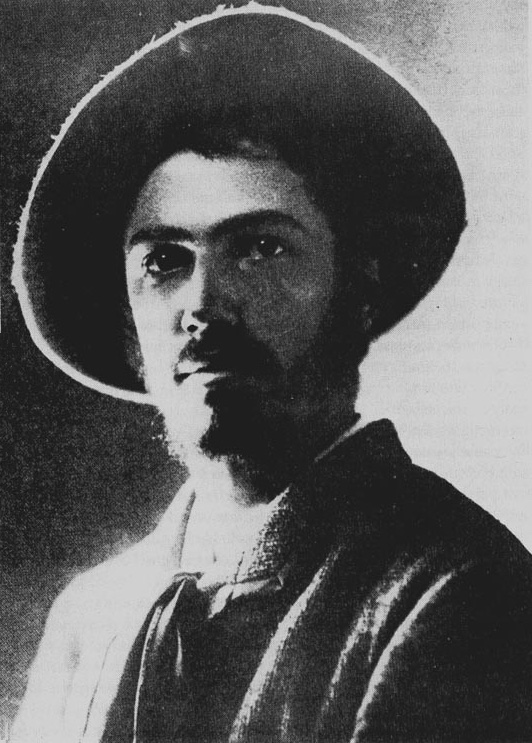

Adophe Appia 1862-1928

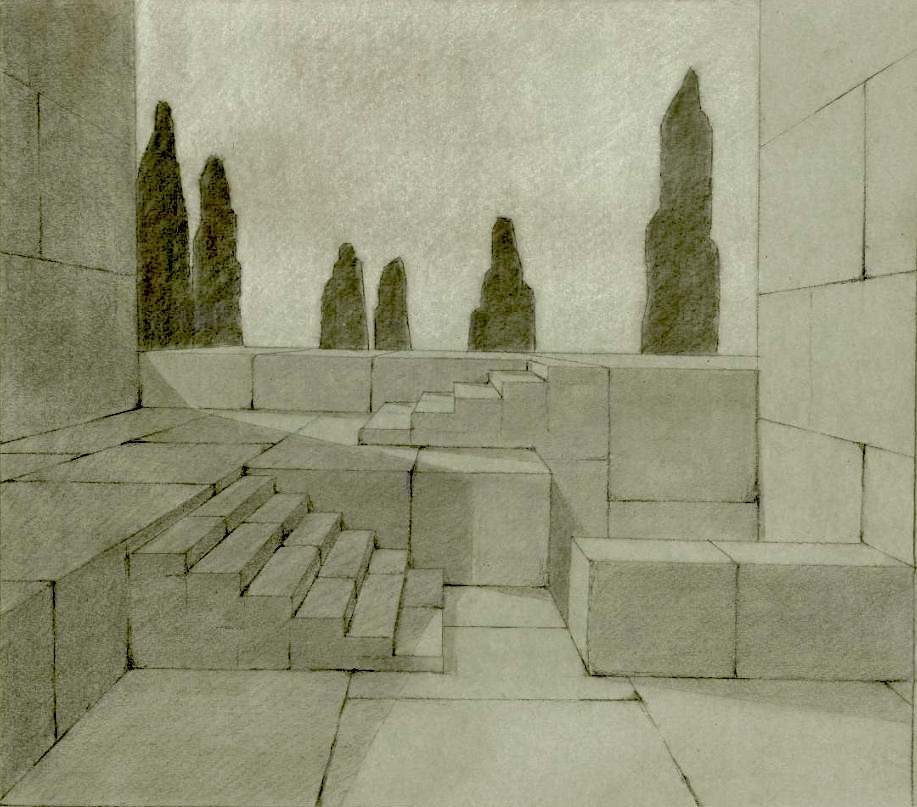

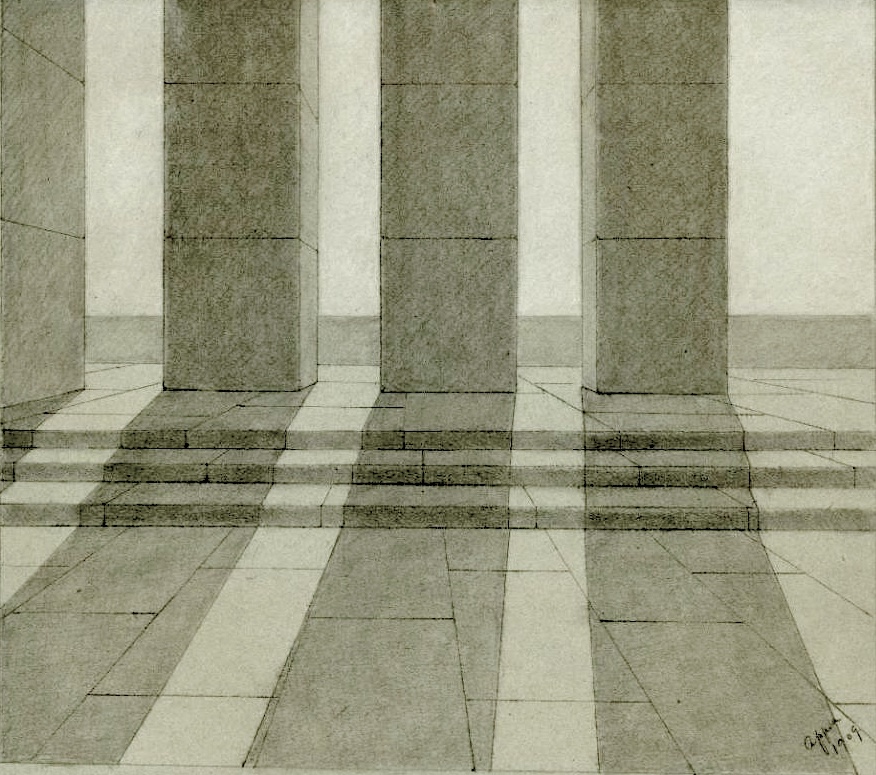

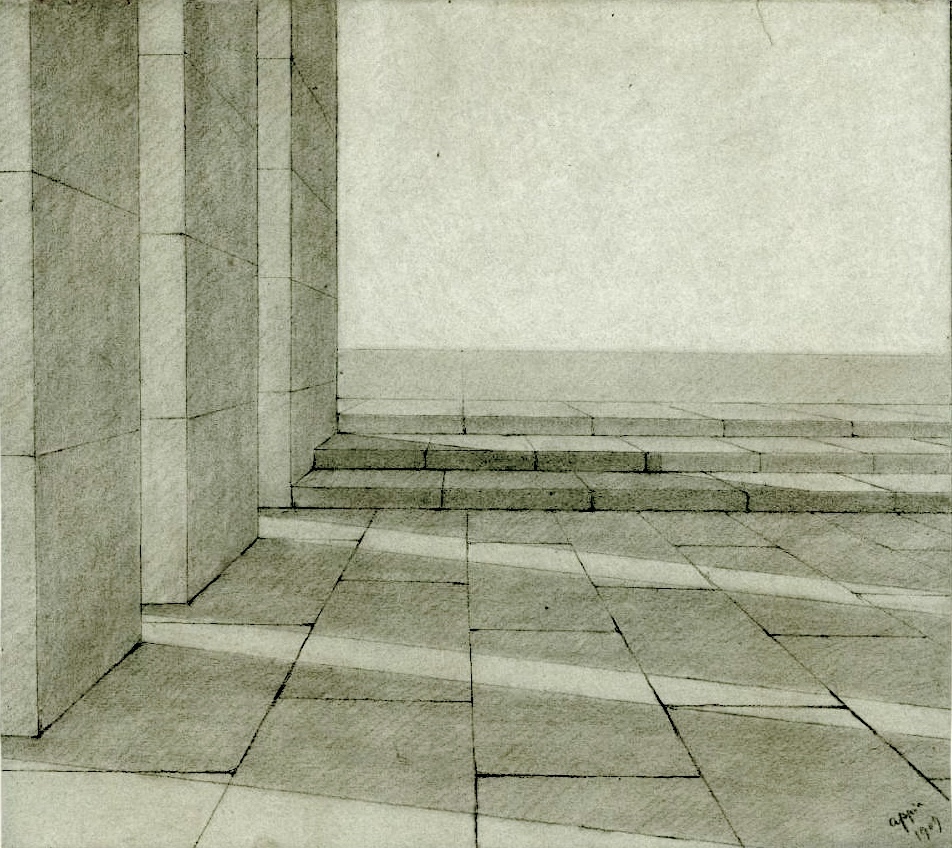

Appia's intent was never pictorial realism, and that is where he parted ways with nineteenth century designers.

He was much more interested in creating a believable mood for the scene. His stage spaces tend to the abstract and

if there are to be real elements, his trees in Parsifal, for instance, they are meant to be symbolic, not literal and are meant to

enhance the mood. And notice how we are drawn through the trees to the light beyond.

All this was very novel and would have been quite shocking to nineteenth century theatre patrons or producers. So much so that very few of Appia's

designs were ever realized. Much of his theory was grounded in Wagnerian music/drama, and while Richard Wagner appeared to have been intrigued

by Appia's ideas, Cosima Wagner, Richard's wife and artistic successor, was outright hostile, and most of his work remained theoretical.

Parsifal, 1896

But it is as a theorist that Appia has been most influential. In La Musique et La Mise en Scéne,

published in 1899, and L'Oeuvre d'Art Vivant in 1921, he articulated his concepts,

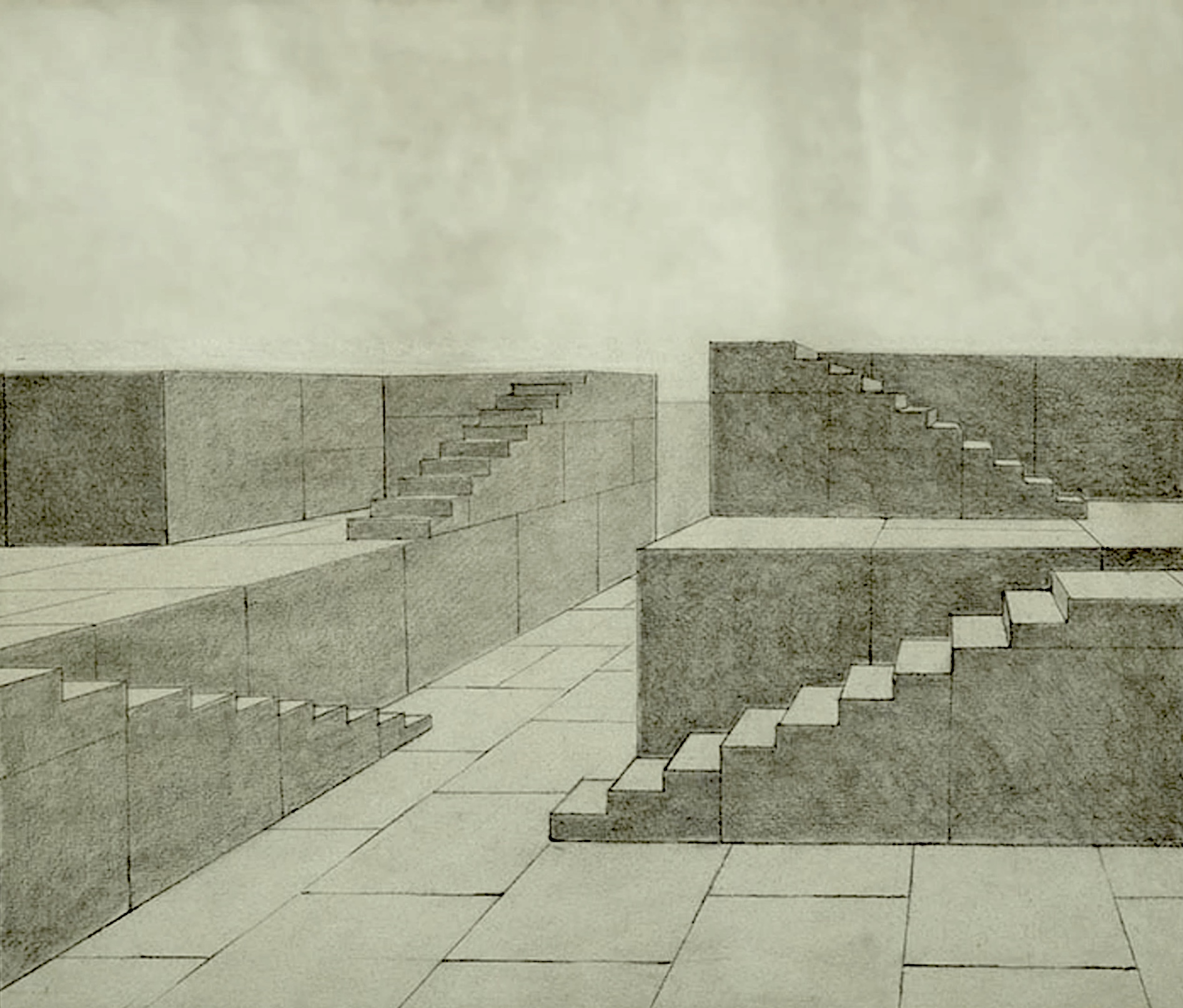

including a series of Rhythmic Spaces.

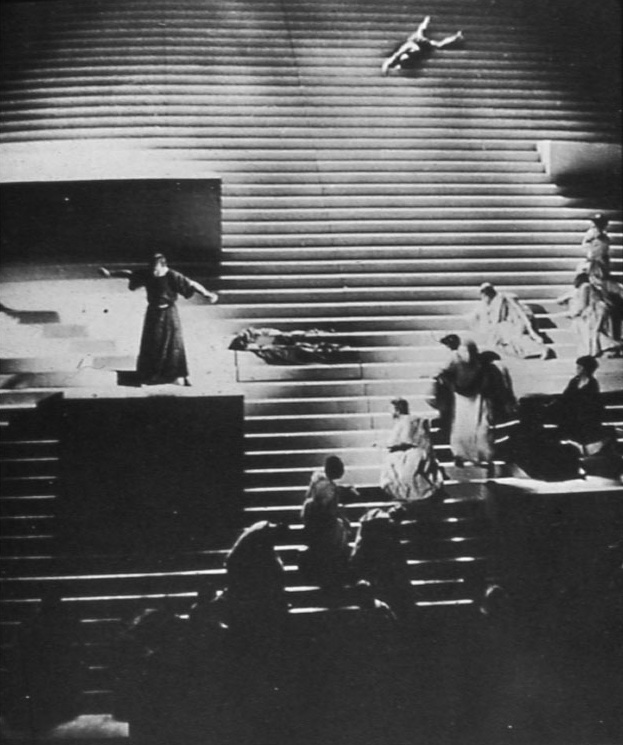

Where his predecessors had demanded broad and elaborate two-dimensional stage pictures, Appia emphasized the three-dimensional potential of the scene.

To do this, he identified four scenic elements including: Painted Scenery (Vertical); Spatial Arrangement (Floor); the Actor; the Light.

His abstract spaces still appear very stark and would have been shocking to an audience accustomed to the picturesque traditional stage painting.

The inclusion of the Actor as a scenic element creates a completely new focus, a more subjective interpretation that had a resonance in modernism.

But it creates a problem for conventional nineteenth century Scenography. Appia correctly observed that painted perspective put the

Vertical Elements at odds with the Spatial Arrangement, for as the Actor moves upstage, the perpective illusion is lost. The Actor is then

limited to moving side to side and cannot be an integral part of any illusion of depth. So Appia rejected the notion of painted scenery

in favour of real three dimensional elements that would allow the Actor move successfully within the entire space.

Oddly though, Appia's renderings do not include any characters. And his relegation of the Actor to just another scenic component

may not have found a lot of favour among leading performers of the time.

Appia's concept of Light as an integral scenic element rather than an added enhancement redefined lighting practice. Appia thought of light as structural, and he distinguished between a diffuse light that allows visible scenery, and a concentrated light that models form. He eliminated footlights which he thought only served to flatten the image, and created novel lighting positions that could properly highlight and model any three-dimensional elements, including the actor.

Rendering for Orpheus , Hellerau, 1913

Orpheus, Hellerau, 1913

Tristan and Isolde, 1896

Tristan and Isolde, 1896

Museé d'Art et d'Histoire

Max Brückner: Tristan and Isolde, Bayreuth 1906

Max Brückner: Tristan and Isolde, Bayreuth 1906

In Fernem Land

Appia also recognized that Light is fliud, the most plastic of all the scenic elements. In his Basel production of Rheingold, Valhalla appears and disappears as a lighting effect. Of course these kind of effects can only be possible by eliminating the standard general floodlights or footlights that defined nineteenth century practice.

Rheingold, Basel, 1924

Swiss Archive of the Performing Arts,

Rheingold, Basel, 1924

Swiss Archive of the Performing Arts,

Appia's drawings have been more successful than his actual productions. Certainly more influential. He had very few productions realized, and if the Basel Rheingold is an indication, theatres must have struggled to convincingly bring his concepts to life.

Rhinegold, Basel, 1924

Walter R. Volbach: ADOLPHE APPIA: Prophet of the Modern Theatre, p.148

So we are back to Appia's publications: La Musique et La Mise en Scéne, and L'Oeuvre d'Art Vivant. His theories found their expression in the work of other designers: Americans Lee Simonsen; Norman Bel Geddes; and Jo Mielziner; and most notably, the Czech Scenographer Josef Svoboda.

Lee Simonsen; Tidings Brought to Mary, New York, 1922

Norman Bel Geddes: Dante's Divine Comedy, Unproduced, 1921

Harry Ransom Center

Jo Mielziner: Faust, Unproduced, 1927

New York Public Library

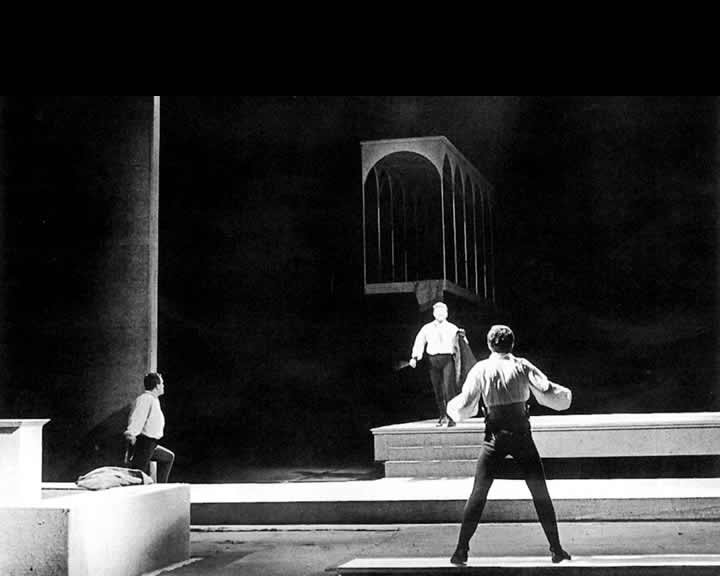

Josef Svoboda: Hamlet, Prague, 1959

Jarka Burian: The Scenography of Josef Svoboda

Josef Svoboda, Oedipus Rex, Prague, 1963

Jarka Burian: The Scenography of Josef Svoboda

Josef Svoboda, Romeo and Juliet, Prague, 1963

Jarka Burian: The Scenography of Josef Svoboda