Adapting The Clerk’s Tale

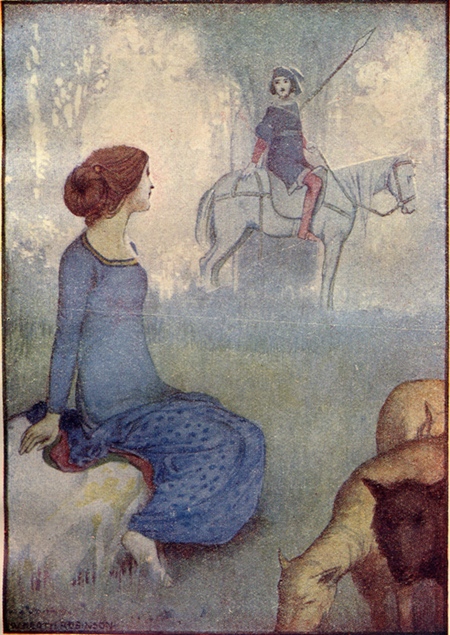

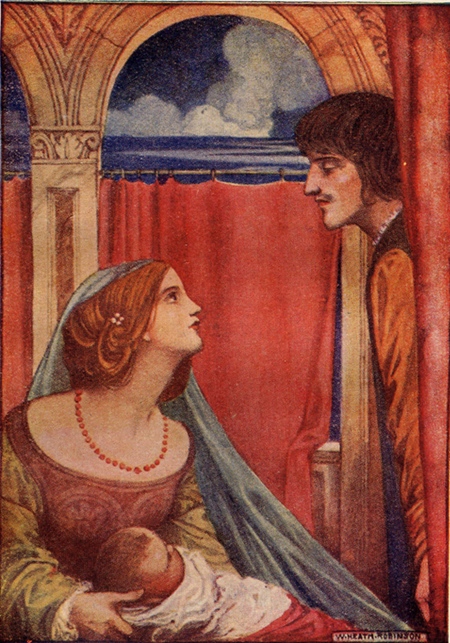

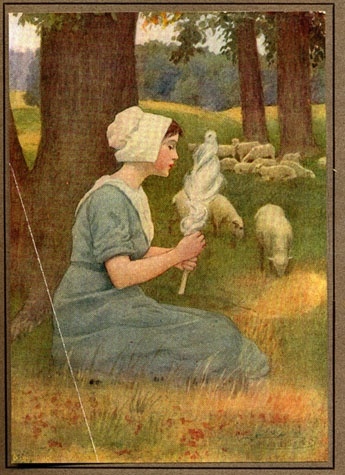

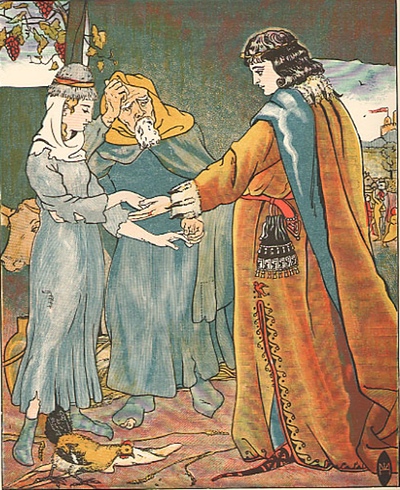

The illustrations above and to the right, by W. Heath Robinson (1872-1944), appear in Janet Harvey Kelman’s Stories from Chaucer in the Told to the Children series. Kelman retold four of the Canterbury Tales, titling each for the female figures in the story:

The illustrations above and to the right, by W. Heath Robinson (1872-1944), appear in Janet Harvey Kelman’s Stories from Chaucer in the Told to the Children series. Kelman retold four of the Canterbury Tales, titling each for the female figures in the story:

Dorigen, the story by the Man of Land

Emelia, the story by the Man of Might

Griselda, the story by the Man of Books

Constance, the story by the Man of Law

Like many 19th- and early 20th-century adaptors of Chaucer, Kelman presents the poet and his period as childlike and innocent:

Very long ago, when children still walked softly through the Greenwood to surprise the fairies, and when big people were as fond of stories as little ones are now, a company of pilgrims went on horseback to Canterbury.

The way was long, and, in order to make it seem less tiresome, the pilgrims tried to find out which of them could tell the best story. A grave and gentle man rode with them. His name was Geoffrey Chaucer. He wrote down the stories in a book, in quaint old English words. You would not know in the least what some of these words meant, although you looked at them all day long.

But here, in simple words, are four of the most beautiful of all those stories that Chaucer tells us big people loved to hear, when the world was young.

It may strike us as odd today that the Clerk’s story of patient Griselda, with its focus on an abusive husband and the (feigned) murder of infants, would be a popular subject for adaptations like this one, but in fact the tale is included in virtually all of the adaptations of Chaucer done for children and juveniles in the 19th and early 20th centuries (by contrast, the Wife of Bath’s Prologue is usually omitted or drastically shortened, and her Tale features in fewer of the adaptations; click here to go the a page on responses to the Wife).

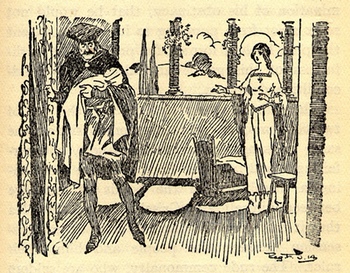

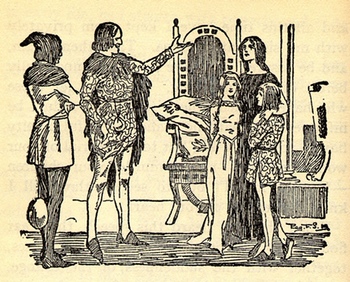

The tenor of the adaptations is usually to stress the morality of Chaucer’s tales: here is what Charles Cowden-Clarke had to say about Chaucer, for example, in his 1833 adaptation (the picture here of Griselda meeting Walter for the first time is from one of the many later printings of this text, this one probably from the early 20th century):

I have endeavoured to put these Tales, written by one of the finest poets that ever lived, into modern language and as easy prose as I could.... My object in presenting them in this new form was, first, that you might become wise and good by the example of the sweet and kind creatures you will find described in them.

The other two illustrations show the soldier taking away one of Griselda’s children, and the reunion scene at the end of the tale. All three of these moments, as you will see, are very popular with illustrators.

As the illustrations from Kelman above suggest, artists were often attracted to the fairy-tale possibilities they saw in the story of the peasant girl who marries the marquis. Warwick Goble (1862-1943) was a children’s book illustrator who in 1912 provided illustrations to The Modern Reader’s Chaucer. While this was not an adaptation for children, his illustrations of Griselda show the same focus on fairy-tale elements. To the left Walter meets Griselda, and below, he marries her. There is no illustration of the apparent murder of the children, but as you will see later on this page, other artists eagerly embraced that subject.

Maria L. Kirk provided the pastoral illustration to the right to a 1914 edition of The Story of the Canterbury Pilgrims Retold from Chaucer and Others, by F. J. Harvey Darton. While most of the adaptations aimed at young people omit the Clerk’s envoy at the end of the tale, Darton included it, thus taking his audience out of the apparent fairy-tale setting of the story.

The tenor of both adaptations and illustrations even to non-adapted editions is, as you will have seen, romantic and, occasionally, pathetic, but there is little to suggest that the tale itself presented challenges to its readers. Not everyone let Walter’s behaviour pass without comment, however. Mary Eliza Haweis did choose to retell the Clerk’s Tale in her Chaucer for Children, but she made a point of drawing a contrast between the situation in medieval Italy and that in England in 1878. To the left and below are her own illustrations to the Griselda story, along with her note to the tale.

Resignation, so steadfast and so willing, was the virtue of an early time, when the husband was really a “lord and master”; and such submission in a woman of the present civilization would be rather mischievous than meritorious. If a modern wife cheerfully consented to the murder of her children by her spouse, she would probably be consigned to a maison de santé, while her husband expiated his sins on the scaffold; and if she endured other persecutions, such as Griselda did, it is to be hoped some benevolent outsider would step in, if only to prevent cruelty to animals.