Adapting The Miller’s Tale

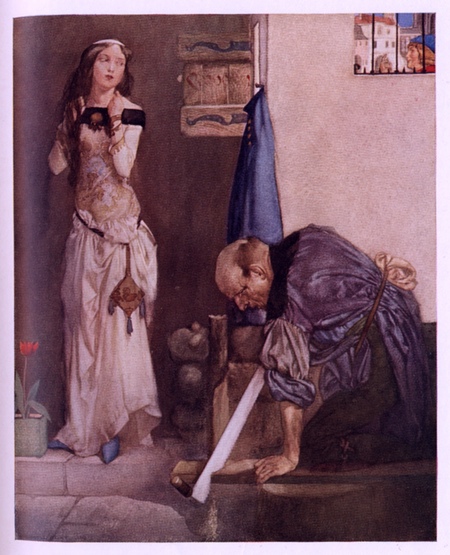

The illustration above is one of Sir William Russell Flint's (1880-1969) paintings to accompany the 1913 Medici Society edition of the Canterbury Tales (theimages appear by permission of the copyright holder, Susan Russell Flint). The illustration stresses the classic fabliau formation of the young wife and the old husband; it is unusual in the period because it was much more common to treat the Miller’s Tale as something of an embarrassment, particularly in the many adaptations for children. In 1878, for example, Francis Storr and Hawes Turner explained to the readers of their Canterbury Chimes that they have skipped the tales of the Miller and the Reeve, for “The tales were good of their kind, but not such as you would care to hear, so I will leave them out.” In the 1914 revision, Storr is a little more expansive:

I must now skip several tales that you will read when you are older. They are all worth reading, for they show us more vividly than any history book can what the English people were like in Chaucer's day; not only the kings and nobles who fought and made laws and levied taxes, but the common folk you meet every day– the parson, the lawyer, the squire, the farmer, the labourer, the butcher, the baker, the candle-stick maker. Chaucer, too, was a poet who saw with clearer eyes than other men. To him nothing was common or unclean. He drew men as he saw them, good and bad alike. Most of the badness you would fortunately not understand, and till you are older it is better for you not to understand it.

F.J. Harvey Darton’s The Canterbury Pilgrims (1904) reduces the tale radically:

The Miller, however, heeded neither him nor anyone else, but told a rude and churlish tale about a carpenter of Oxford.

This carpenter, so the story said, was persuaded by a clerk that there would be a second great flood, and that if he wished to be safe from drowning he must make himself an ark. So he used his kneading-trough as a sort of boat, and was hoisted in it up to the celing of the kitchen. When the water began to rise, the clerk told him he was to cut the cords that held the ark, and drop into the flood, and sail safely away. He did exactly as he was told, and for a little while hung quietly up in the air, close to the roof, waiting for the deluge in a state of great fear and wonder. Suddenly he heard someone crying, “Water!” He cut the cords, thinking that the flood had come, and down he fell to the hard floor, breaking his arm, and getting nothing but laughter for his folly.

Just as they drew near the carpenter’s house, Nicholas bethought him of a new dance. He was so merry that he whirled and capered to show off his steps to Alisoun, quite forgetful of the lighted torch he was carrying, until the flame blew aside in the wind and caught one of Alisoun's ribbons which began to burn. “Water, water!” cried the wife.